Rukhmabai Raut: Child Bride to Colonial India’s First Woman Doctor

She became fatherless at 8. With her widowed mother then transferring her property to her daughter’s name, she became the owner of her parental property at 8. At the age of 11, she became a child bride, married to 19 year-old Dadaji Bhikaji Raut. At a young age, she became the victim of a lengthy legal case that turned not only in her favor but also future generations! The legal case she was embroiled in led to the enactment of the Age of Consent Act, 1891. She attained her physician degree from the London School of Medicine. She was the first practicing woman doctor in colonial India. We are delving about the brave and bold Rukhmabai.

There is an interesting story behind her ambition to become a doctor and her qualification thereafter. She belonged to a community of carpenters. After her father Janardhan Pandurang’s death, her widowed mother Jayantibai remarried after her marriage at 11. Rukhmabai did not shift to her in-laws’ place. Her step-father Assistant Surgeon Sakharam Arjun supported her choice. After Dadaji Bhikaji Raut’s repeat requests to take his wife home turned vain, he filed a court case against her in 1884, i.e. when she turned 20. Meanwhile, Rukhmabai started writing letters regularly in newspapers under the pseudonym ‘A Hindu Lady’ on her plight. She won the support of many readers. In one of her letters, she expressed her desire to study medicine. Readers supported to fulfill her ambition. Her mother and step-father also supported her. A public fund was created wherein supporters donated to fund her travel and study in England at the London School of Medicine. Subsequently, she went to England and returned to India as a qualified doctor.

What led to the enactment of the Age of Consent Act in 1891? Why did Rukhmabai not shift to her husband’s place? Initially, Rukhmabai did not shift to her marital home because she was too young and she did not want to leave school. Her husband had an aversion to education. Besides her school books, Rukhmabai also brought books on myriad subjects from the local library to study. She also regularly accompanied her mother to the weekly meetings of the local Prarthanä Samäj and the Arya Mahilä Samäj. She thus evolved into an intelligent and cultured young woman.

Rukhmabai desired to go back to her marital home after she completed her education. Later she changed her decision never to go back to him. She found her husband’s character questionable. Her husband Dadaji Bhikaji Raut lost his mother at a young age. He started living with his maternal uncle. The environment there was disturbing and Rukhmabai did not wish to live in such a milieu. His uncle had a mistress at home, which led to repeat quarrels leading to a suicide attempt by his aunt.

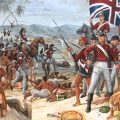

Rukhmabai’s step father supported her decision. With her husband filing a case against her in 1884, a series of more court cases ensued. She provided grounds for refusing to start her marital life, seeking help of lawyers Payne, Gilbert, and Sayani. Her legal case led to major public discussion on child marriage and on the rights of women. A public uproar resulted. Child marriage, purdah system, Sati, and Jauhar held sway in the Indian social fabric after the widespread atrocities by Islamic plunderers on Indian women and female children. It is but unfortunate that feminists blame ancient Indian society for this instead of blaming the oppressors. Instead of showing the oppressed as the victims, oppressors are shown as victims and as oppressed.

In one of her letters to Times of India under her pseudonym ‘A Hindu Lady’, on June 26, 1885, Rukhmabai wrote:

“This wicked practice of child marriage has destroyed the happiness of my life. It comes between me and the things which I prize above all others – study and mental cultivation.Without the least fault of mine I am doomed to seclusion; every aspiration of mine to rise above my ignorant sisters is looked down upon with suspicion and is interpreted in the most uncharitable manner.”

This is an extract of her letter. Her write-up was later reproduced in the book Child Marriages in India by Jaya Sagade.

The court gave Rukhmabai two options – to either go back to her husband or face imprisonment. Rukhmabai preffered imprisonment rather than remaining in a marriage that she did not want. Ultimately in 1888, her husband accepted monetary compensation for dissolution of their marriage. The two parties thus came to a compromise. Rukhmabai was thus saved from imprisonment.

It was after this that a public fund was raised to support her medical education. She was also financially supported by many a well wisher for her education. London School of Medicine followed by obtainment of higher qualifications at Edinburgh, Glasgow and Brussels! And he became a doctor in 1894. Rukhmabai started working in a women’s hospital in Rajkot. She continued writing against child marriage and women’s seclusion (purdah) and became actively involved in social reform activities. She never married again. She died in September 25, 1955 at the age of 91.

Featured image courtesy: Wikipedia and google.