Gurukulas and Universities – When the Civilized World Sent Its Best Students To India

Just a thousand years ago, India was dotted with gurukulas, universities and myriad varieties of educational institutes where students gathered to gain credentials in advanced education. Most people today have heard of only Takshashila and Nalanda, but there were scores of institutes and even today, excavations are revealing more centres of learning. The land was home to the finest ecosystem of knowledge propagation which gave utmost importance to scholars, students, books and erudite discussions.

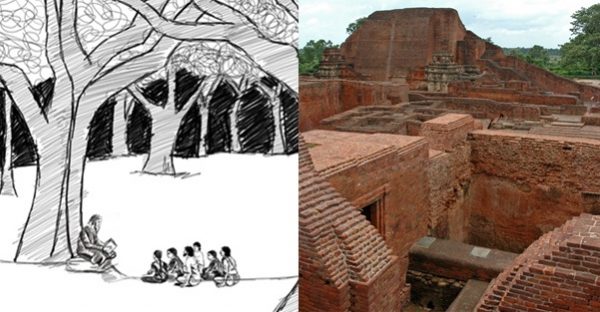

When Tagore started an open-air school at Shantiniketan in 1901, which later went on to become a famous university, he was one in a long line of educators from India who believed that holistic learning could only be obtained in the midst of nature under the close supervision of a parent-like guru.

India’s earliest teachers were the gurus who taught in gurukulas and ashrams located far away from the hustle and bustle of towns in what could be called forest universities. It is no surprise that the Vedas, which are the earliest known oral books containing the thoughts of a highly civilised society are replete with exquisite references to nature and the concept of inter-dependence of living organisms. To these gurus, it was important for humans to realise their humble status in the infinite universe before embarking on the long journey of learning.

Not all gurukulas were in forests though. Many were in villages and towns, since the gurus were usually householders with families. However, secluded locations were preferred.

Over time, the systems of transmission of learning to newer generations got institutionalised and gave birth to famous universities such as Takshshila, Nalanda and the famous temple universities of which the remains are still found in southern India. A sizeable number of foreign students came to study in India from China, Korea, Japan, Indonesia and West Asia. While the most famous names are Fa-Hien and Xuanzang (Hieun Tsang), who left behind detailed accounts, there are scores of others who made difficult journeys by foot and on board ships just to imbibe knowledge from Indian professors. Many of the foreign students copied texts and commentaries to carry back to their countries. The rush for gaining an education from the Brahmins and Buddhist scholars of India was similar to today’s rush to study in or be certified by American and European universities.

There is a curious hesitation among modern historians to refer to India’s multi-disciplinary centres of traditional learning as universities. This comes from the excessive importance given to the written word, to solid buildings with established pedagogy and rigid systems of certification. Thus, the talented but bare-chested and dhoti-clad engineers and architects of ancient India who built incredible irrigation canals, rainwater harvesting structures, palaces, forts, roads, dams and aqueducts are barely acknowledged as professionals. Similarly the medical practitioners of yore who knew which combination of herbs could help in healing diseases, where to procure them in forests, how to conduct complex surgeries and additionally possessed spiritual insights are often regarded as quacks or witch doctors.

Learning was a sacred, important duty

Ancient Indians were deeply invested in gaining perspectives about “the material and the moral, the physical and the spiritual, the perishable and the permanent”. During the process of gaining these perspectives, they made important discoveries in the sciences, mathematics and applied medicine. The sacredness of learning is evident from the large number of Sanskrit shlokas that deify the guru such as “Acharya devobhava” (Taittiriya Upanishad). Initiation of children (both male and female) into the alphabets for the first time was done ceremonially in most parts of India. Even today, the ceremony survives in the Haathekhori in Bengal (performed during Saraswati Puja) and the Vidyarambha in Southern India (when children are asked to trace alphabets on rice). The sacred thread ceremony or the Upanayanam ceremony performed for Dwija children between the ages of eight and 12 customarily marked the beginning of education. Traditionally, it was considered unethical to barter knowledge for money. Gurus usually took a token gift (Guru Dakshina) in return for the long years of knowledge they imparted.

Chinese student Xuanzang has left a touching account of the love of learning in India. It was not forced but came naturally from the seeds of curiosity planted in childhood. He found ascetics who devoted their entire lives to learning and teaching simply for the love of knowledge be it in sciences or philosophy and to the exclusion of every comfort. Such men, who also adhered to high moral standards, were held in high esteem by the State but did not care for any honour bestowed on them. The practise of bhiksha (requesting for food from households which is incorrectly called begging in modern times) was common among these ascetics and was regarded as a perfectly respectable activity. Xuanzang mentions that dedicated scholars preferred poverty to affluence and did not even heed the ties of domestic love. They knew no fatigue and travelled across the country to lecture and share their knowledge. Thus, there was a system that ensured a steady supply of qualified persons who gave themselves up to a life of learning and service to the land while keeping their needs to a minimum.

Listen to Sahana Singh speaking on the topic of India’s educational heritage:

The forest universities of Ancient India

The Mahabharata gives examples of famous ashramas such as Naimisha, which was a forest university headed by Saunaka. Other hermitages mentioned in the epic are those of Vyasa, Vasishtha and Visvamitra. One hermitage near Kurukshetra even mentions two female rishis. Among Vyasa’s famous disciples were Sumantra, Vaisampayana, Jamini, Paila and Suka.

Rishi Kanva’s hermitage is not mentioned as a solitary unit, but an assemblage of numerous hermitages around the central one presided by Rishi Kanva. There were specialists in every branch of learning cultivated in that age; in each of the four Vedas; in Yagna-related literature and art; Kalpa-Sutras; in the Chhanda (Metrics), Sabda (or Vyakarana), and Nirukta. There were also Logicians, knowing the principles of Nyaya, and of Dialectics. Specialists in physical sciences and art also taught their skills. The art of constructing altars of various dimensions and shapes for conducting yagna was regarded as significant and this required the teaching of Solid Geometry. Other topics that were taught included properties of matter (dravyaguna) and physical processes. Zoology was also a subject.

Physician Susruta, author of Susruta-Samhita, the most ancient treatise available on general medicine and surgery laid out that in order to be a successful physician, one must be well-versed in many sciences. His might well be the earliest call for an inter-disciplinary approach to a subject.

एकं शास्त्रमधीयानो न विध्याच्छास्त्र निश्चयम्

तस्माद्वहुश्रुत: शास्त्र विजानीयाच्चिकित्स:

A physician who has learnt one science only cannot be sure of his own science (Ayurveda) and for this reason the physician has to be versed in many sciences.

Thus, the forest universities laid out an entire spread of subjects that imparted a holistic view of the world as it was then known. There were no artificial demarcations between religion and science and often, one led to the other.

This article is an excerpt from Sahana Singh’s book The Educational Heritage of Ancient India – How an Ecosystem Of learning Was Laid to Waste.

Click here to buy The Educational Heritage of Ancient India – How an Ecosystem Of learning Was Laid to Waste.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely of the author. My India My Glory does not assume any responsibility for the validity or information shared in this article by the author.