Godse’s Verdict on Gandhi; Partition that Displaced 11 Million

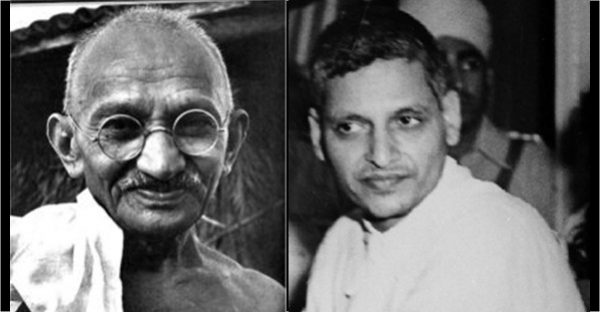

Nathuram Godse’s condemnation for the murder of Mahatma Gandhi cannot detract from the extraordinary cogency of his critique of Gandhi’s political strategy throughout the independence struggle and a fundamentally misconceived policy of appeasing Muslims regardless of long term consequences. Historian Koenraad Elst has entered this crucial debate on the murder of the Mahatma with a skillfull commentary on the speech of Nathuram Godse, to the court that sentenced him to death, the verdict he preferred to imprisonment…..

Godse continues his analysis by zooming in even more closely on Gandhi’s role and responsibility in the political equation which led to the Partition. His intention is to trace Gandhi’s fateful mistakes one by one, and to show how they inexorably prepared the ground for Partition. At the same time, he tries to show how Gandhi’s mistakes conformed to a pattern that betrayed a peculiar type of personality:

“This section summarises the background of the agony of India’s partition and the tragedy of Gandhiji’s assassination. Neither the one nor the other gives me any pleasure to record or to remember, but the Indian people and the world at large ought to know the history of the last thirty years during which India has been torn into pieces by the Imperialist policy of the British and under a mistaken policy of communal unity.

“(…) virtually the non-Muslim minority in Western Pakistan have been liquidated either by the most brutal murders or by a forced tragic removal from their moorings of centuries; the same process is furiously at work in Eastern Pakistan. One hundred and ten millions of people have become torn from their homes, of which not less than four millions are Muslims, and when I found that even after such terrible results Gandhiji continued to pursue the same policy of appeasement, my blood boiled, and I could not tolerate him any longer. (…)”

By “one hundred and ten millions” is probably meant “one hundred and ten lakhs,” i.e., eleven million, a reasonable estimate of the number of persons displaced by the Partition. By any standard, this wave of refugees amounted to a terrible failure of Gandhi’s policies, yet the Mahatma is not known to have criticized his own policy decisions in terms of their role in the escalation towards Partition.

“The accumulating provocation of 32 years culminating in his last pro-Muslim fast goaded me to the conclusion that the existence of Gandhiji should be brought to an end immediately. On coming back to India [from South Africa] he developed a subjective mentality under which he alone was to be the final judge of what was right and wrong. If the country wanted his leadership it had to accept his infallibility; if it did not, he would stand aloof from the Congress and carry on in his own way. Against such an attitude there can be no half way house; either the Congress had to surrender its will to his and had to be content with playing the second fiddle to all his eccentricity, whimsicality, metaphysics and primitive vision, or it had to carry on without him.”

By Gandhiji’s “metaphysics” and “primitive vision,” Godse means the seemingly irrational concepts like “soul force” and the “inner voice” which Gandhiji routinely invoked, and which took the place of cool strategy. “Eccentricity” refers to Gandhiji’s gimmicks, such as his half-naked dressing habits, which were all the more bizarre given that Gandhiji, unlike most Indians, had worn cumbersome Western suits, ill-adapted to the Indian or African climate, for decades. Winston Churchill, a man of the world who was comfortable with ethnic peculiarities, considered the “half-naked faqir” Gandhi as outlandish even for an Indian.

“Whimsicality” seems to refer to the lack of strategic consistency in his policies, which drifted from one extreme to another, e.g., from abject collaboration with the British to head-on confrontations; from letting intra-Congress democracy take its own decisions (e.g., the election of Subhas Bose as Congress president) to challenging those very decisions by means of ostentatious fasts; from boycotting the 1931 census count to accepting power divisions based on the resulting census figures; from promising to stake his own life for the prevention of Partition to meekly accepting the Partition on the plea that “the people” had chosen it.

A glaring example of Gandhi’s whimsical policy shifts is his changing the course of the Civil Disobedience Movement of 1930-31. The agreed aim of this mass agitation was complete independence, nothing less. Yet Gandhi threw the movement into disarray by suddenly formulating far more modest demands. These were mostly conceded and included in an entirely individual pact between himself and Viceroy Lord Irwin (March 1931): promise of future parleys on constitutional reform, release of prisoners, restoring confiscated property.

R.C. Majumdar, the leading historian of the freedom movement, reports: “The Pact caused a great disappointment to many (…) The main points of their opposition were summed up by Subhas Bose (…) Subhas Bose’s criticism met with general approval at the Youth Congress (…) Gandhi himself issued a statement to the effect that ‘the victory belongs to both the parties,'”—a quintessentially Gandhian explanation.’ When Jawaharlal Nehru saw the terms of the Pact, he was disappointed: “Was it for this that Our people had behaved so gallantly for a year? Were all Our brave words and deeds to end in this? C..) in my heart there was a great emptiness as of something precious gone, almost beyond recall.”‘

Majumdar nonetheless credits Gandhi with one undeniable long-term gain, viz. the Viceroy’s readiness to treat Congress as an equal negotiation partner for the first time. A few weeks later, Congress at its Karachi session also ended up approving the step which Gandhi had unilaterally taken, though “the resolution of the Congress endorsing the Pact is a curious example of self-delusion and an attempt to mislead the people” (obscuring the Pact’s continued acceptance of British control over vital matters like defence, foreign affairs and finance). Gandhi had to force a reluctant Nehru to sponsor the resolution; the self-delusion and attempt to mislead were Gandhi’s own input. The Congress delegates’ ultimate submission to Gandhi’s will cannot alter the fact that Gandhi had undemocratically overruled the will of Congress, whimsically imposing an unexpected new direction on the freedom movement.

The above article is an excerpt from the book Mahatma Gandhi and His Assassin, authored by Koenraad Elst. The author, a Belgian orientalist and Indologist, is well known for his writings on Indian History, Hindu-Muslim relations, and comparative religion.

Click here to buy Mahatma Gandhi and His Assassin.

Featured image courtesy: Goodreads and Pinterest.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely excerpt from a book. My India My Glory does not assume any responsibility for the validity or information shared in this article as excerpts from the book.