The Trauma of Being an Infidel in Kashmir: A Psychologist Reflects

The Infidel Next Door by Rajat Mitra is a book on Hindu identity and resurgence. It tells the story of two boys who live in a temple and a mosque in Kashmir. Anwar sees Aditya as an infidel and wants to throw him out of Kashmir unless he converts. The story captures the nature of the historical conflict between Islam and Hinduism in a way that left me spellbound. This is a story you can’t remain indifferent to.

Reading this book was an experience for me that I will never forget. It is similar to the novels of Bankim Chandra that raises one’s passion. I re-read parts of it. The characters are real and may take you on a journey to discover what it meant to be a Hindu, even give a feeling that you may have read the story before.

This book is about life, about growing up, about identity, loss and resilience. In today’s troubled times of Sabarimala and Ayodhya, it may not be an easy read but tells that there is hope and redemption.

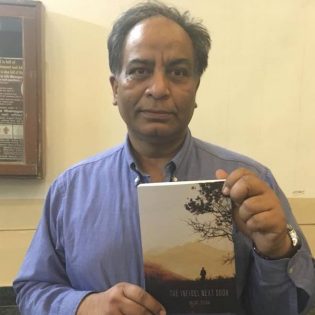

The following interview took place on a sunny afternoon over endless cups of coffee and gave me insights into the mind of the author. Rajat Mitra, the author of The Infidel Next Door, is a psychologist turned author with a rich experience of having worked with terrorists, refugees and survivors. He told me his father loved literature and books were his best friends. In this interview he combined his psychological insights with the books that have influenced him to tell me a story reflective of our times.

Maneesh Guha: How long did it take you to write The Infidel Next Door and how did you find the time?

Rajat Mitra: Almost four years. And I wrote it in between my work and while travelling across the globe. I have written it sitting in many places, amongst them in war zones, while staying in monasteries, in a refugee camp, in a Sikh temple and while waiting to talk to someone in a prison.

Maneesh Guha: Your book has three important messages. The first is that there is a rising Hindu consciousness in the present century and Hindus are in grief having moved away from denial after centuries. The second is that there is an emerging rage that may lead to a mass movement. The last is that Hindus in earlier times resisted to this civilizational onslaught and were not passive beings who accepted the atrocities.

Rajat Mitra: Yes. There is a rising Hindu consciousness and my book The Infidel Next Door is topical in that sense and relevant for the times. As a society the Hindus are far more aware than ever before in the past and there is a rage that will rise more as they become aware of the injustices on them. But I also believe that the rising Hindu consciousness will not be violent and destructive as some people make it out to be. When understood, this consciousness will also lead to healing and closure for the entire race and lead to peace.

This rising Hindu consciousness will also lead to a new Hindu identity, someone like Aditya, the protagonist of my novel, who combines the best of his religion and discovers that while going in search of his roots. It may also lead to those of other religion to define their identity like Anwar and Zeba and question issues like indoctrination and bigotry.

But I do believe that very soon we may witness a movement by Hindus to find a new collective consciousness, to redefine their identity and find a place in the new century.

Maneesh Guha: As we discuss this there is news about the Supreme Court delaying to hear the Ram Janma Bhoomi case once again. One of the themes of your book is the silent trauma that Hindus have faced over the destruction of their temples and the delay in getting justice. To me this resonates with the theme of the book. Would you like to comment?

Rajat Mitra: In my opinion one of the deepest grief for the Hindu society has been the attempts to destroy their civilization, their culture by invaders. The Hindu society is in denial about its grief and has not expressed it either symbolically or collectively. It is ironical because in several societies, the trauma otherwise known as trans-generational trauma has been discussed in depth and led to healing dialogues between sworn enemies. I hope my book may also raise awareness and contribute to healing for the Hindus.

Maneesh Guha: There are very few works of fiction based on Hinduism as a religion or protagonist who is a Hindu priest. We have Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse or The Razors Edge by Somerset Maugham. In one the hero is on a search for ‘if death is the end of all human existence’. Your book tells us about a Hindu man who goes on a search for his roots in a land of his ancestors from where they were forced to flee for refusing to convert. Refusing to convert and give up their faith in the face of death by Hindus is a side rarely known to today’s generations. Why it is so?

Rajat Mitra: The protagonist of The Infidel Next Door is on a search for his roots and comes to build a temple in Kashmir. He wonders why Hinduism and Islam cannot coexist in peace not realizing that his is not a proselytizing religion while the other is exclusivist that demands total obedience and submission to only one God. My book will tell people not only of this difference but of the Hinduism that once existed in India and faced the invasions. To me there are two Hinduisms, one that gave the world the Vedas, the Upanishads and the scriptures and the other that struggled for survival for over a thousand years. Many intellectuals berate it forgetting it was dharma alone that helped it survive.

Hinduism has often been written about as a regressive religion by writers and has been described as one with bizarre practices, esoteric ways rather than its philosophical meanings and wisdom. Even the struggle of Hindus to defend themselves and the struggle by its priests’ lies buried in obscurity. The adherents of Hinduism are portrayed as semi-literate, of regressive mindset who need to be brought out of its morass of ignorance. If that was so, how did this religion, their civilization emerge after a thousand year old wound? My book explores this injustice.

In the present times the Hindu priest doesn’t evoke the reverence that he deserves for having preserved his religion. To me he is not only the bearer of ancient traditions but one who saved his religion from annihilation.

Maneesh Guha: The Infidel Next Door in my opinion is also a political novel with a message. When Aditya goes back to his destroyed temple in Kashmir and faces Anwar who sees him as an infidel, he is speaking perhaps for millions of Hindus who are grieving for their broken temples. Does it have a similarity to Anandamath, Bankim Chandra’s most celebrated novel?

Rajat Mitra: In both the novels, Hinduism is facing threats and their young protagonists fight a lone battle. While Bankim Chandra in his book described India as a mother Goddess, Aditya’s going back to his temple in the face of certain death is that of a Hindu saint who can’t see his faith destroyed.

This is a time of rising nationalism in India. An emergent Hindu identity is emerging with Hinduism standing at crossroads today. While the Abrahamic religions, communism and Islamic proselytizing is trying to attack its very foundations, the Hindus must form a collective to survive from this onslaught. The Hindus may not be a colonized race today like they were in Bankim Chandra’s time but a slave mindset and fragmentation runs deep, the same as in Bankim’s time.

Yes, the two books may have a similarity in that they may spread a nationalistic message that I had not thought of earlier when I began to write. If it does, I will be proud of it. When I began writing I had based it on relationships, a bildungsroman novel on growing up. It was also on exodus faced by Hindus in 1990. But as I penned my words, deeper layers of meaning emerged that I had not have been aware of. I accept that with humility.

There is need for a renaissance for the Hindu psyche to get over the fragmentation and become a collective, to become a political being to save his identity. The enemy here is within and that is our fear of ourselves, an emotion that I express through the struggle of Aditya.

Maneesh Guha: Is it because the intellectual discourse in India has been Marxist oriented and the educational discourse has been designed by scholars who tried to give it a slant?

Rajat Mitra: Yes, I believe it is very much so. One of my childhood experiences was the puzzle that the lessons I read in school about Muslim rule, the freedom struggle didn’t match the stories I heard at home from parents. Something did not seem to match and it seemed someone was trying to hide something. As I discovered, it was the official narrative that I was supposed to believe as correct.

Knowing that I was writing a book which had a theme on destruction of a temples and how Hindus protected their religion, many of my friends warned me saying it will alienate you.

Maneesh Guha: Has it alienated you?

Rajat Mitra: Yes.

Click Here to buy The Infidel Next Door by Rajat Mitra.

Maneesh Guha: You had a tough time getting your book The Infidel Next Door published and had to approach many publishers who turned your manuscript down. Why was it so? How many rejected your MS? How did you go through that period?

Rajat Mitra: It was a tough time for me writing endless queries and letters. Almost forty to fifty publishers rejected it. As I understood talking to a few of them, they felt it didn’t fall within the parameters of the Indian novel that had a format in everybody’s mind. Many felt that it won’t sell because of its theme of the struggle of Hinduism against iconoclasm. Second they said its protagonist being a priest and one that glorified martyrdom of Hindus will not cut any ice with most readers who have a leftist mindset. One of them even suggested he will consider it if I make Hinduism look a little more esoteric and regressive.

Few of the journalists read it. Privately they told me they admired the book, its language, its message and uniqueness but because of the editorial policy would not be able to review it for their paper or their magazine.

It was Midwest Book Review who were the first to read my book it and sent me an in-depth review. A world famous peace activist and Nobel nominee, a nun, professors from universities sent their review after reading it. Their feedbacks kept me going.

Finally Utpal Publications took on the publication of the book in India and elsewhere.

Maneesh Guha: Why did you write a novel and not expressed your ideas through non-fiction?

Rajat Mitra: Fiction to me can express a truth deeper than a work of non-fiction in ways that the latter can never achieve. Fiction can reach further in the human mind in exposing a truth that lies buried and hidden. While non-fiction tells us what had happened in past, fiction tells us what it must have felt like for those who went through it. While non-fiction tells events that happened, fiction captures the imagination, the passion to make us empathize with the people of that time. Today, when we need to understand why our ancestors struggled and martyred themselves for the sake of Hinduism, it is fiction that can help us. ‘We have many a buried emotions that are lurking in the subconscious,’ as Carl Jung put it so beautifully. There has been a serious dearth of fiction of that kind in India that will make us question our past as taught to us, empathize with our ancestors and history and may lead to a closure where there is trauma. Colonialism destroyed our ability to empathize with our roots and fiction can bring it back.

The British banned novels that had the possibility of making Indians nationalistic and question their submission to the empire. They realized that the novel as a medium could make people aware of being slaves and give them a voice. They realized that the fiction and songs like ‘Vande Mataram’ can arouse the masses and unite them to fight. The culture they built continues till this day and the education being in the hands of a select few after independence didn’t allow it to change. So, today we don’t have novels that can fulfill that role in India like in many other cultures that has made them sensitive towards larger issues that chains them. Few authors write about sensitive issues that are in denial, are unresolved and need closure. I notice often there is a lamentation about forgetting our heroes, their martyrdoms, our past but we can only let it happen in an environment of free thinking and intellectual inquiry. I believe when inner transformation begins to take place in India, fiction will play a major role in bringing about the change in consciousness.

Books like Dr. Zhivago told the world about people’s need for individual space and freedom under communism. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich told about the tragic life in Gulag. Things Fall Apart told the world about the way white Christian missionaries destroyed the African native culture and civilization. Roots told the world about the trauma of black men and women forced and brought to America and the evils of slavery. Non-fiction would have never achieved that.

Maneesh Guha: You say Indians lost the ability to empathize due to colonialism and slavery and we still continue that culture. You further believe that it is fiction that can bring it back, let us find the identity of the race where we lost it. Is there such an example elsewhere?

Rajat Mitra: Yes, the works of authors like Toni Morrison, James Baldwin led to understanding of Black identity in the aftermath of slavery. Like that of Chinua Achebe and Nadine Gordimer did that in South Africa. They all led to a resurgence of identity for the whole race before it was destroyed. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee did it to the Native Americans and the books Exodus and The Last of the Just did it for Jews.

Maneesh Guha: You draw a comparison between Jews, Blacks and Native Americans and the Hindus. Where is the similarity?

Rajat Mitra: The similarity lies in the extermination, the genocide and the annihilation they all faced in different periods of history. Will Durant talked of the genocide and destruction of Hindu civilization but he was forgotten and ignored by Marxist historians.

Maneesh Guha: What are your views about Ram Janma Bhoomi? Does your book promote the construction of the temple over the disputed site?

Rajat Mitra: A famous writer once said that the people who climbed on the dome of the Babri masjid to break it wore jeans and T-shirts. I am forgetting who said that but I guess he said that to point out that the people who did so were modern and not of a regressive mindset. I would like to add to that. To me it is immaterial what they wore but it represents the grief reaction of a society that had laid buried and emerged after centuries of denial and injustice. It was an outpouring of grief of a people who had seen their cherished symbols and structures razed to the ground. I felt pained when our leaders went on a defensive to say they were ashamed or someone called it the darkest day of his life. To me it shows the complete absence of an understanding of grief of their own society and its negation with the leadership being unable to take ownership for the grief they carried.

It is time that Hindus understand and accept their grief and take ownership of that and stop feeling guilty.

I had once mentioned in an audience how Native Americans would gather around their sacred sites and it would turn into anger. Everyone empathized with that and said it is but expected against white atrocities but if you give this analogy for and how the mosque was built on a sacred site for Hindus, there is avoidance. This hypocrisy must go.

Maneesh Guha: Does the conflict between Aditya and Anwar symbolize the conflict between Islam and Hinduism in general? There is a chapter in which Anwar walks into the temple and later Zeba to watch a Hindu ritual and are filled with disturbing feelings about the idea of God. How did you conceptualize that?

Rajat Mitra: The conflict between the two is the fundamental difference between the basic tenets of monotheism of Islam and the plurality of Hinduism. It is about how to define God and whether he is exclusivist or not. The way Anwar sees this issue has been the dilemma of perhaps many Muslims over centuries except that now you cannot destroy idols so easily as you could do in medieval times. While iconoclasm has led to the desecration in India on a scale unimaginable to the rest of world, it also led to a trail of memories for the present generation that hasn’t healed. My book is to find healing from that wound that still remains in our consciousness. It may exist for many Muslims who converted from Hinduism on what their ancestors did but find it unable to express it.

Many Muslims have shared the utter sense of confusion and despair as a child when they encountered a deity for the first time or saw Hindu rituals. Many of them shared being taught to feel hatred and disgust by their elders and turned their faces away. It is true for many recently converted Christians many of whom call it ‘devil’s worship’. It bothers me to see this level of hatred and animosity that exists towards Hinduism.

Maneesh Guha: The way and manner in which Aditya prays is mystical, symbolic and has a resonance to in that it symbolizes the relationship between the deity and the priest in Hinduism. Would you comment on that in the light of Sabarimala issue?

Rajat Mitra: The relationship of Aditya to his Shivling, to his deity in The Infidel Next Door, is very representative of a Hindu priest with his deity and one that has been the same for thousands of years. For a Hindu priest his idol is a living entity who breathes and lives in the temple and means everything for him from guiding him through his loneliness to providing him with answers through meditation.

The Hindu way of praying in the temple cannot be compared to either the Christian prayer hall or the space in the mosque where Muslims do namaz. A Hindu praying space is not a prayer hall at all. It is a living space in which deities are bonded and seen as a manifestation of the Supreme being who has been brought to life through puja and rituals. This is what Anwar and Zeba fail to understand the first time when they come to the temple and it is something they come to understand later. At first it is deeply distressing for them as they have been taught that any relationship with the divine can have only one meaning and any other is sacrilege.

Maneesh Guha: Sure that discovery is captured very beautifully in later chapters especially when they walk in the ruins. But their visit to the temple, their being next door doesn’t lessen their faith in their own religion but enriches it. Why?

Rajat Mitra: Yes because they realize that religion is more than dogma and rules. It is an inner faith and conscience that lives in the human heart and shines independently of it. A path that follows its independent logic and that no religion can destroy and is higher. The relationship with God takes on being a personal journey not bound by any doctrine and that is what the central message of my book is. The realization of God comes through an inner search by empathizing with the views of another man’s faith.

Maneesh Guha: I went through many strong emotions while reading the book and even stayed awake the whole night finishing it. Some parts of the book referred to parts of myself that I had not been aware of. Is that a reaction you expect your readers to go through? Do you expect people of different religions to respond differently?

Rajat Mitra: I feel touched that my book The Infidel Next Door affected you so deeply. People belonging to different religions have said that they found the story touching their heart, at times deeply disturbing. A Christian nun read the book and said she felt closer to Hinduism and wondered why adherents of such a religion even need to convert. A Muslim professor read it and felt that it may help many belonging to his religion to turn away from violence. Several Kashmiri pandits who read it felt it was their individual story of exile and why their civilization didn’t die. Many Hindus have said it removed the shame they felt in calling themselves a Hindu.

I believe people from so many religions find it so close to their heart because Aditya’s troubled relationship with God symbolizes everyone’s relationship with God.

Maneesh Guha: The Infidel Next Door, I would say, has some human values and choices that we face during the choice between good and evil. When Aditya and Nitai decide not to abandon their temple risking death or Zeba tries to protect the life of a man she loves is more important than her inner desires, they are being altruistic. Do you really think human beings can truly make such an inner choice when faced with evil and are not bound by compulsions and inner logic?

Rajat Mitra: Yes they can. The question of evil is one of the most profound and troubling one in religion. Hinduism sees evil not as opposite of goodness but as ignorance of not knowing your true self. On the other hand monotheistic religions see it as diametrically opposite to goodness or God. When faced with the question of evil, both Aditya and Anwar make choices based on what they have been indoctrinated with but soon find that it leaves them fragmented to begin an inner journey for its true meaning.

Maneesh Guha: The Infidel Next Door book has many similarities that are close to books like ‘The Kite Runner’ by Khaled Husseini, in theme, ‘Things Fall Apart’ by Chinua Achebe, ‘Siddhartha’ by Hermann Hesse and ‘The Razor’s Edge’ by Somerset Maugham. But at the same time it is rooted in the ethos of India. One of the things the book brings out is the way priests saved Hinduism. Can you talk about it?

Rajat Mitra: Yes the priests were in charge of the temples and tried their best to prevent their desecration. They never ran away from invading armies but stayed back not leaving their deities as they were living beings for them. Their lives ebbed away often while putting their arms around the stone deities as they often bled to death. This is one of the most poignant images I learnt while writing the book and forever changed the way I saw the Hindu priests and their valor. It filled me with a pride I didn’t have in my religion. A priest whose ancestors died like this told me this story.

Maneesh Guha: One of the central attractions of The Infidel Next Door for me is the relationship between Aditya and Zeba. They belong to different religions and get drawn to each other. Aditya is a loner with a deeply feminine side of compassion while Zeba is an orphan who loves his prayers and him from a distance. Why does she leave Aditya fragmented when she sees him ready to give up everything for her?

Rajat Mitra: As a poet once said, “Unrequited love is one of the deepest expressions in man.” Aditya teaches Zeba to live, to have faith in herself and Zeba understands that such a man cannot be her husband. She tells him that he is like those distant peaks that look beautiful but one can never possess. She closes the room and waits in darkness because she can’t open the window and see him outside because then she knows she will run to him.

Maneesh Guha: Who were your influences in authors, in psychology?

Rajat Mitra: Vivekananda, Thoreau as philosophers whose writings inspired me. Martin-Baro as a psychologist whose liberation psychology opened my eyes and who worked with the downtrodden in South America before getting killed. In writers I have many. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Nadine Gordimer, James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, Chinua Achebe and lastly Manto, Premchand and Tagore’s poetry that have influenced me.

Maneesh Guha: Three of your favorite sentences from the book?

Rajat Mitra: “A shelter always remains a shelter. It never becomes a home.”

“History is like an empress, angry with a whip in hand who demands obedience to the written word. Memory is like a mother who holds us in embrace when our soul needs answers.”

“I saw you then standing alone lost to yourself and understood what the word forever meant.”

Maneesh Guha: Have you personally changed as a person as a result of writing The Infidel Next Door?

Rajat Mitra: Yes, I feel I have discovered myself as a person and my roots. I started to write this book in the midst of a most difficult phase of my life. I had relocated to a new country, left behind an institution and had a family to support. I was feeling lonely, hurt and alienated. Writing the book was healing, a solace that I found in those difficult times and it helped me to turn inwards and ask questions about my own self about human condition. It started while clearing up my study table. I felt the notes I had written from my days of working with people as a psychologist who had told me their stories. It was as if they were telling me to write a book, to give them a voice and why their stories need to be told. It was a mystical experience.

About Rajat Mitra

Rajat Mitra is a clinical psychologist who has worked with Islamic militants and radicalized youth on one hand and survivors of mass violence and genocide on the other. He holds a PhD in psychology, is a social entrepreneur and was given the Ashoka fellowship for working on criminal justice reforms in India.

The many narratives he heard over a thirty-year career of providing support for human rights violations and abuses, gave him psychological insights into two of the most disturbing issues of our times as to how do radicalized youth cope with religious indoctrination and how does psychological trauma of survivors gets passed on as narratives from generation to generation.

Rajat Mitra

While studying for a course by Harvard, Rajat became aware of the deep link between trans-generational trauma, collective memory and the effort to preserve them through poems and literature.

An avid reader of literature, he didn’t realize how and when these different feelings began to take shape and form characters in his mind who began to live and breathe through him telling him a story that he felt was the voice of a people that had become silent and gone unheard.

The Infidel Next Door is a moving story that he believes will speak directly to all people whose conscience has ever been shaken by religious persecution in our times. Rajat is currently working on a de-radicalization program for youth.

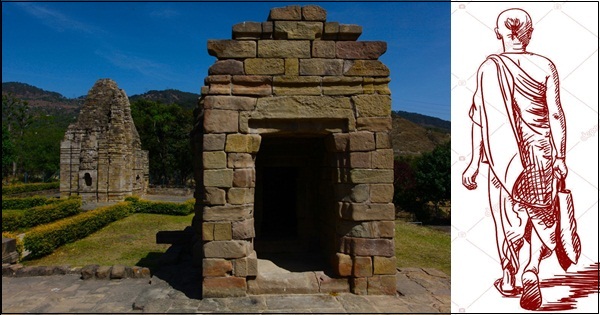

Featured image (for representation purpose only) courtesy: Ajay Jain (kunzum.com) and depositphotos.com.