Bhishma of Mewar: The Story of Chundawat Clan; Epitome of Patriotism

श्रेयान्स्वधर्मो विगुण: परधर्मात्स्वनुष्ठितात् |

स्वधर्मे निधनं श्रेय: परधर्मो भयावह: ||

It is far better to perform one’s natural prescribed duty, though tinged with faults, than to perform another’s prescribed duty, though perfectly. In fact, it is preferable to die in the discharge of one’s duty, than to follow the path of another, which is fraught with danger.

– Bhagavad Gita- Chap 3- verse 35

Several centuries ago, a young lad, hardly 18, prince of one of the most illustrious kingdoms was heir apparent to the throne- a post anyone would die for. All was going well when destiny decided to turn tables. The prince sacrificed his claim to the throne to his half-brother who will be born of the marriage of his father and another girl. Not only this, he also took the oath that he would forever remain loyal to the kingdom and that none of his descendants would stake claim to the throne.

You might be thinking of Bhishma Pitamaha, but this answer is about Rawat Chunda, the Bhishma of Mewar.

Early 15th century Mewar was very prosperous, was being ruled by Rana Lakha. His first son was Chunda. Rao Ranmal of Marwar had come with an alliance of his sister, Hansa, to the crown prince of Mewar. But due to a sequence of events (We shall not go into it right now, there are two different stories about this, See * below), It was decided that Rana Lakha would marry Hansa. The short-tempered Ranmal was adamant that Hansa will be the mother of the future Rana of Mewar. To settle matters, Chunda sacrificed his claim to the throne and also declared that his successors will not stake claim to the throne.

Chunda became the Rawat of Salumber and established the Chundawat dynasty. The Rawats of Salumber continued to play an very important role in the state affairs of Mewar till the time of Maharana Amar Singh. As James Tod remarks ‘the first place in the councils, and stipulating that in all grants to the vassals of the crown, his symbol (the lance) should be superadded to the autograph of the prince. In all grants the lance of Salumbar still precedes the monogram of the Rana’.

The story does not end here.

A study of the descendants of Rawat Chunda is even more interesting. Rawat Chunda himself outlived his half-brother Rana Mokal and continued to help Rana Kumbha establish his authority in Chittor. His son took part in battles against Nawab Muhammad Shah of Malwa and Nawab Ahmadshah of Gujarat, he also took part in an attack on Nagor along with Rana Kumbha.

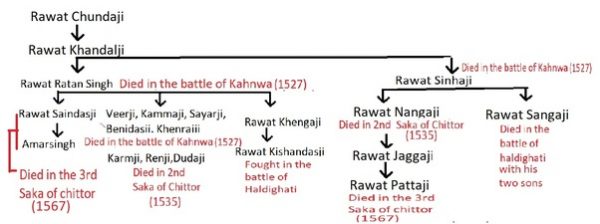

Notice the family tree above.

These were the prominent Chundawat chieftains of the 16th century who all laid down their fighting the invaders.

We can notice here that Ratan Singh along with five of his sons and his brother fought in the battle of Khanwa with Rana Sanga against Babur. The Battle of Khanwa saw the valour of over 300 of the Chundawat clan.

In 1527, when Maharana Sanga was injured in the battle of Khanwa, he was taken away from the field. The warriors requested Rawat Ratan Singh the chief of Salumber to personate the Rana and assume the insignia of royalty in the latter’s absence. The patriotic chief, whose motive was to serve the state to the last drop of his blood, declined to do so for his forefathers Chunda had relinquished it for ever.

7 years later three of his other sons and nephew would take part in the 2nd Saka of Chittor fighting against Bahadur Shah, Sultan of Gujarat, as Maharani Karnavati led the Jauhar.

Suraj Pol in Chittorgarh where Nangaji died defending the fort in 1535 and Saidasji died in 1567

The valor of Rawat Patta (with his mother and wife) and Rawat Saidas in the 3rd Saka of Chittor against Akbar is well documented.

Rawat Patta was sixteen when he was given the reins of Khelwa, their estate, his father had fallen in a battle.

In 1567, when Akbar raised the seize of Chittorgarh, Salumbar Rawat Saidas fought bravely at the Suraj Pol.

Rawat Patta was given the post of ‘Adhipati’ and after Akbar shot Jaimal, led the forces. His valor has been noted even by the Mughal historians. His mother- Songara Rani Sajjan Bai and his wife- Rathore Rani Phool Kanwar of Merta too took part in the Saka.

In the words of James Tod, When Salumbar fell at the gate of the sun, the command devolved on Patta of Kelwa. He was only sixteen:his father had fallen in the last shock, and his mother had survived but to rear this the sole heir of their house. Like the Spartan mother of old, she commanded him to put on the ‘saffron robe,’ and to die for Chittor: but surpassing the Grecian dame, she illustrated her precept by example; and lest any soft ‘compunctious visitings’ for one dearer than herself might dim the lustre of Kelwa, she armed the young bride with a lance, with her descended the rock, and the defenders of Chittor saw her fall, fighting by the side of her Amazonian mother.

Rawat Kishendas and Sanga who fought in the battle of Haldighati. Pic credits: Deeptangan Pant (@cynicalpahadi) | Twitter from Moti Magri,Udaipur

For centuries, they fought and fought and nothing came between them and their fight for independence. The Chundavat dynasty again and again proved their loyalty to their motherland. Hundreds of men sacrificed their lives protecting their country.

In my view, they were more loyal to Mewar than even the ruling Ranas and princes as several of them over the course of time went to the Mughals due to family feuds. This is definitely one of the best examples of Sacrifices I have ever read about.

The legend of Hadi Rani is also based on the Chundawats of Salumber. The story goes like this- The Salumber prince married a Hada princess and a few days later, Maharana Raj Singh called him for duty, for a war against Aurangzeb. Having married only a few days ago, he was hesitant to go. But Rajput ideals and Kshatriya dharma compelled him to go to war. He asked his wife for a memento before leaving.

The princess felt that she was an obstructing his path to do the duty for country, that he would be thinking about her during the war, cut her head and told her servant to present this to the prince. The prince was devastated upon learning this, nevertheless proud went on to win the war. Even after winning, he lost all desire to live and gave up his life.

*The story as to why and how exactly Lakha married Hansa has two different narratives in James tod’s and in the Vir Vinod. However, the story by James Tod is more famous.

Sources and further reading-

1. James Tod: Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan- Vol 1

3. Vir Vinod- Vir Vinod Vol. I : Singh, Ratna : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

4. Nainsi khyat- https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.345960/page/n61

5. Jaimal Vanshprakash- https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.309083

This article was first published at landofsevenrivers.wordpress.com (all images sourced from this original article).