How 83-Year-Old Ropuiliani Challenged British in Mizoram in 1892-’93

The Swadhinata Sangram of Bharat saw the mass participation of women on an unprecedented scale, but unfortunately, several of them remain invisible, unknown and unsung in the heap of our history textbooks that have been written in post-Independent India. Such is the story of Ropuiliani of the Lushai Hills (present-day Mizoram). It goes back to the time when the British were establishing their authority through either territorial annexation or forcible military occupation of one province after the other. It needs to be mentioned here that Mizoram was officially known as Lushai Hills until 1952. Christianity is the predominant religion in Mizoram today. On Sundays, the numerous Churches dotting the enigmatic landscape of Mizoram become all agog with different activities pertaining to a religion that came to be known here only in 1894.

After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the colonial occupation of Bengal was complete. Since the East Bengal provinces of Sylhet and the Chittagong Hills were located at the border of the Lushai Hills, the Lushais now came into contact with the British more frequently than before. Later, when under the clauses of the Treaty of Yandaboo (1826) Assam was annexed into the British Empire, the hill districts adjoining the plains of Assam also came under the purview of the British authorities. Prior to the arrival of the British in the Lushai Hills, the people lived in a conglomeration of independent units (villages) under the control of a chief called Lal, on whom all power of land and people was vested. The Lal appointed a council comprising of elderly men called Upa to advise and assist him in the day-to-day affairs of the community and the village administration. Decisions were usually arrived at by the consensus of this council which met in the house of the Lal. The opinion of the strongest warriors (thangchhuah) in the village exerted a considerable influence on these decisions.

After the annexation of Bengal, there was a gradual expansion of trade relations between the adjoining hills and the British-occupied districts of Cachar, Sylhet, and the Chittagong Hills. People residing at the border of the Lushai Hills were entering into the territory of the Lushais for business and trading purposes. This was, however, not to the liking of the Lals who staunchly resisted the intrusion of outsiders into the region. They were made to pay a safety tax to the chiefs and accept their supremacy over the region. In this way, the Lals were stripped of their political powers, e.g. they could no longer wage wars and collect tributes of various kinds. The first instance of Lushai conflict with the British took place in the year 1826 when a group of woodcutters from Sylhet (in present-day Bangladesh) who entered the region were attacked, because they refused to pay the safety tax to the Lal in whose territory they had cut down the trees.

This incident rattled the British administration. A commercial blockade was soon imposed on the markets with which the Lushais were carrying out their trade. The Lushais also retaliated with counter-attacks. In January 1871, they killed Winchester, the planter in Alexandrapore tea garden in Cachar and also imprisoned his 6-year old daughter Mary. This was followed by the Chin-Lushai Expedition of 1889-90 after which the area was annexed into the dominions of British India on administrative grounds. The Lushai chiefs of various clans used to undertake invasions and retaliatory expeditions to save their territories from British incursions. The arrival of the British in this region was accompanied by certain significant changes in the social, cultural, and religious aspects of the people’s lives along with the administration.

The Colonizing Mission of the Church

The advent of Christianity and western education in the Lushai Hills brought about far-reaching changes in the religious beliefs of the Lushais, which were essentially based on nature worship (often referred to as ‘animism’ in the Western academic vocabulary). Christian missionaries developed the idea that all that is associated with the traditional religion and culture of the Lushai society was pagan, and hence not fit to be followed anymore by the new converts to Christianity. Tension was brewing among the neo-Christian converts as to whether they should abandon or retain their traditions, customs and culture. Dialogue between Christianity and other religions was totally rejected for it was seen as “un-Christian”. It came in the way of the evangelist mission of converting, saving souls, and church planting. This was a vast change in the traditional beliefs and practices of the hill people, which was not accepted and welcomed by them at ease.

The first missionaries who visited the Lushai hills were young Presbyterians who had already undertaken evangelical works in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills of Meghalaya. At this time, Aizawl was a major trading centre and the hub of various janajati communities like Khasis, Jaintias, Nagas, Mikirs, and Kukis. The Christian missionaries learnt the Lushai language, translated the hymns and teachings of the Bible and the New Testament into Lushai so as to spread the Gospel of Jesus among the people of the hills. The Bible became a convenient cultural weapon for both the colonizer and the colonized. While the missionaries saw it as a tool for civilizing and rescuing the degenerate heathens (non-believers), a few sections among the colonized employed it as a weapon of reprisal to justify the whole edifice of imperialism. E.g. a young Lushai chief named Khawvelthanga who studied at the mission school and became a believer, used the Bible to argue against some traditional cultural and ritualistic elements that were in vogue among the Lushais.

Accordingly, the natives were made to believe that without the Gospel, all cultural values of the heathens are inadequate, incomplete and imperfect. The Christian missionaries also developed a Lushai script based on the original Roman script, which later laid the foundation of education among the locals. A printing press was set up at Aizawl that published works on Christian literature. Charity in the form of medical services and education was thus enmeshed with evangelism. The establishment of an administrative power structure based on colonial interests, conversion of the Lushais into the Christian faith, and the rapid socio-economic change brought about by colonialism permeated through the entire socio-political fabric of the Lushai Hills. Both health and education now came to be equated with Christianity, which constituted an inseparable part of the colonial design of political occupation and territorial annexation.

Earlier, the people worshipped their own Devtas called Pathian (Creator of the Universe, Pa meaning the masculine), Khozing (Preserver of the Universe), Khuavang (identical to Pathian but inferior to him in the Lushai religious pantheon), and Khuanu (the Mother Goddess, Nu meaning the feminine). They believed that some harmful spirits called Huai resided in the old trees, mountains, rocks, caves, and streams, and to whom all illnesses and misfortunes were attributed. The Puithian (village priest) was respected and revered as he had a cure for all evils and misfortunes in the form of different religious rites and rituals involving agni (fire). These beliefs were systematically being replaced by faith in the Almighty or Jesus. The missionaries projected the patriarchal concept of God and displayed a discriminatory attitude towards women in their understanding of religion. In the later years, Pathian was culturally appropriated as the new Christian monotheistic God.

The concept of ‘sacred groves’ and the animals within these groves such as tigers and pythons were held in high esteem by different clans among the Lushais. Hence, they could not reconcile with the changing circumstances after the British imposed arbitrary taxes on these lands too, in order to fatten the coffers of the Company. The slow but steady increase in the number of Christian Lushais in the hills soon became a cause of worry for the Lals. It took some time for the hill people to understand the consequences of what was actually happening. British military officers in the 1850s recorded a series of periodic raids in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The Lushais who inhabited the hills south of Silchar frequently raided tea plantations because traditionally, this territory formed their hunting grounds and they felt that the colonial masters had unnecessarily intruded into their space. These raids soon became a cause of both threat and concern for the British.

From the mid-19th century to the last decade of that century, bloody wars were fought between the Lushais and the British. The daring and fearless Lushais became a source of terror for the British officials who were seated in the neighbouring low-lying hills and the plains of Eastern Bengal and Assam. These persistent intrusions led to punitive British military expeditions between 1850 and 1892. Successive expeditions were launched by the British from 1871 onwards in the Lushai Hills, which witnessed the active participation of a number of chiefs and chieftesses against the British subjugation of their territories. Among them the role of Pi Lalnu Ropuiliani is commendable, in that she sacrificed her own life for the grater cause of her own people. She led one of the most forceful resistance movements against the British in general and colonial Christianity in particular. A born rebel, it was Ropuiliani who first blew the trumpet of revolt in the Lushai Hills.

A Veerangana is Born

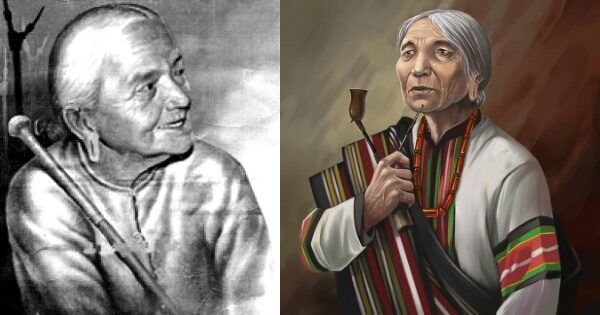

As per the recorded history of the Lushai Hills dating back to the late 19th century A.D., it was after the death of her husband Vandula that Lalnu Ropuiliani became the first woman Chieftess of a village called Denlung, situated near Hnahthial in present-day Southern Mizoram. The village still exists today. At that time, the womenfolk in the Lushai society were bestowed with the right to become the chief if her husband (who had been the village chief) had deceased. This means that when the reigning chief died, their widows acted as regents, and reigned on behalf of their minor sons who occupied the vacant throne left behind by their fathers on account of death. Besides Ropuiliani, there were many other such chieftesses such as Pibuki, the widow of Manga who was the chief of Durtlang, Lalhlupuii, the widow of Lalngura and the chief of Sentlang, etc. This practice had been followed until the abolition of the institution of Chieftainship in Mizoram in the post-Independence era.

The immediate result of colonial expansion in the Lushai Hills was an increase in the number of female chieftesses, mainly widows. It heralded a radical transformation of women and politics in the socio-cultural sphere of the Lushai Hills area. Military Officer J. Shakespear noted the condition of the Southern Lushai Hills in 1892 – “It is noticed that all these villages except Mualthuam and Aithur are now ruled by widows.” There is very scant literature available in the public domain on the life history and the struggles of Lalnu Ropuiliani against the British. Born in 1806, she was the daughter of the great chief Lalsavunga Vanhnuailiana of present-day Aizawl. She was married to Vandula, the son of Tlutpawrha and the grandson of Rolura Sailo, the famous chief of Haulawng and who was also once the ruler of the entire Southern Lushai Hills. Ropuiliani was thus the daughter-in-law of a ruling chief’s family with a respectable social status and reputation.

She inherited her exceptional warrior-like qualities and an uncompromising anti-colonial attitude from her father and as well as her husband Vandula who was the chief of Ralvawng, a place in the Southern Lushai Hills. Ropuiliani succeeded her husband after his demise in 1889 at Denlung, and ruled her people initially from the village of Ralvawng. Her husband having opposed the British in their attempts to suppress the Lushais, she carried forward his holding her head high. Since the period of her father and later her husband, Ropuiliani was resentful of the British imperialist policy to annex the Lushai Hills. She sternly refused to acknowledge the supremacy of the British colonialists and their authority over the Lushai Hills and its people. She also played a pivotal role in influencing the other chiefs to resist the British annexation policy. In due course of time, Ropuiliani emerged as a formidable opposition against the British. Gradually, she was able to establish her influence and undisputed control over nine different villages situated in Southern Mizoram at present.

The expansion of territorial control by the British in the forested mountains went in tandem with the rapid spread of Christianity. Transformations were already taking place in the entire structure of the Lushai society ranging from marriage rituals and social norms after the conversion of the Lushais into the new religion. Changes also came to be reflected in the Lushai dressing styles and costumes, dance and music, food and lifestyles of the people. E.g. the use of drums in different religious festivals was considered “inappropriate” by the Church for the shaping of a good Lushai Christian. Sometimes, these same drums were made to appear like Church bells in order to shape and reaffirm the Lushai Christian identity. Introduction of new practices by the Church changed the everyday life of the inhabitants of the Lushai Hills.

Another visible change took place in the agricultural practices of the people who were beginning to give up jhum or shifting cultivation. In the early 19th century, the mountainous region that is now recognized as Mizoram looked perilously inhospitable and frighteningly wild to the British officers. Thickly wooded cliffs rose like tall spires everywhere and the intractable jungles provided habitation mostly for predatory wildlife. In the depth of this wilderness existed spaces where small-scale, mobile human communities practiced hunting, jhum cultivation, and a seemingly impressive martial culture. Occasionally, the hillsmen traded tusks and timber for salt and metals with the plainsmen. Soon, the British extended their control over all forests and declared them as state property. Some forests were classified as Reserved Forests for they produced timber which the British wanted for building railway sleepers.

It was in these forests that people were not allowed to move freely, practice jhum cultivation, collect fruits and roots, or hunt animals. Under various policies of forest conservation, the colonial government declared a strict prohibition on jhum cultivation in different parts of the Lushai Hills, and permanent cultivation was introduced in the valley areas. It was because shifting/jhum cultivation depended upon the free movement of people within forests which were essential for their survival. Restrictions were aimed at checking this freedom of movement of the people to use their land and forests in the way they wanted for growing crops, hunting animals or gathering forest produce. This further helped to strengthen the hold of the colonial administration in the Lushai Hills. E.g. no wet-rice cultivation under the shifting cultivation method was permitted without a valid pass signed by the District Officer.

The British were now faced with widespread protests and hence, they ultimately had to allow the people the right to carry on shifting cultivation in some parts of the forest. It was decided that jhum cultivators would be given small patches of land in the forests which they would be allowed to cultivate on the condition that those who lived in the villages would have to provide labour to the Forest Department and also look after the forests. Ropuiliani vehemently protested against such undue interference of the foreigners in the society. The Lushai Hills were finally incorporated into the colonial empire in 1890, i.e. towards the latter half of the 19th century. The British officials imposed forced labour and house tax on every village and its people. This policy was met with fierce resistance from the Lals, because any Lal who disobeyed the British law was either convicted and imprisoned or his chieftainship was forcibly taken away.

Ropuiliani’s Fight to the Finish

In 1892, a few British officials led by the Bawrhsap (Political Officer) toured the whole of the Lushai Hills. They met with and spoke to all the Lals and made peace with them. But, the terms of this forced peace and agreement rested upon “You must pay taxes” and “You must become coolies”. The Lushai chiefs were never accustomed to being ruled by anyone and they enjoyed supreme power over their territory. They thus committed themselves to the task of protecting their motherland with all the best possible efforts. The role of Ropuiliani was now becoming prominent. The British were planning to construct a road from the Chittagong Hill Tracts via the territories which were then under the control of Ropuiliani extending uptil the Chin Hills of Myanmar. The Lushai chiefs who had still held on to their territories, including the widow chieftesses, were now in a dilemma and forced to negotiate with and make certain adjustments with the colonial government. Ropuiliani was quick to grasp the intentions of the British Government behind such a step.

She knew that her villages would have to supply a large number of labourers for the purpose of the road construction. She therefore strongly opposed the construction of the roads and urged her followers to stay away from engaging themselves in any work under the authority of the British. She narrated to them the stories of their glorious past. This was done in order to invoke pride among the natives for their own culture and traditions so as to counter the religious evangelist mission of the Church. When the British officials came to one of the villages under Ropuiliani’s control with the aim of collecting taxes and labourers, she informed them that she was the owner of the village and that she would never tolerate the unwanted intrusion of any outsider there. She also told them that she would neither send any of her men to work as labourers in the road construction project of the British nor would she let them pay any taxes.

The British officials had organised several meetings (Chief Durbar) of the Lals, which required the attendance of all of them. But, Ropuiliani strictly refused to attend any of them. She said – “My subjects and I have never paid any tax to anyone, neither have we done any forced labour. Let them be Kings and Princesses in their own lands; this had been our land since the time of our ancestors, they should not come here and trouble us. We must evict and chase out any and everyone who is an alien.” She lived by them till her last breath. Ropuliani never paid any of the taxes that the British collected, levied or imposed. The secret activities of Ropuliani and the political aim of her movement to retain the independence of all the villages in the Lushai Hills and drive out the British, became a cause of worry for the British officials.

Earlier too, they had always suspected her to be the root cause behind the emergence of anti-colonial resistance movements in the Lushai Hills and its neighbouring areas. She was even accused of having been involved in many attacks of the British troops by the Lushais at that time. Ropuiliani and one of her associates Pasaltha Khaungchera, played a very important role in these attacks. As the movement slowly began to intensify, the British officials decided to act. Ropuiliani was identified as the main culprit behind the way in which the affairs had been unfolding in the hills for some time now. Thus, an expedition was dispatched on August 7, 1893 under Captain J. Shakespear to subdue Ropuiliani’s village and her youngest son Lalthuama who assisted his mother from the very beginning in accomplishing her mission. They were supported by another Lushai chief Dokulha Chinzah. But, he was captured too early and spent a large part of his life in prison.

All the important Lals of Vandula’s clan were dead by now. Lalthuama therefore became the recognized head. He was completely under the influence and control of his mother. She always prevented him from abiding by the instructions and orders of Captain John Shakespear, who succeeded C.S. Murray as the Superintendent of the South Lushai Hills from April 15, 1891. With the intention of protecting and defending the Lushai Hills, both mother and son resisted the British till the end. While they were residing at Ralvawng, the British came and demanded coolies from her to work for them at cheap rates. They also asked for chickens, crops and various other goods which she had outrightly denied. She said, “This freed slave should not say anything to us. His face is loathsome and revolting in my sight. I do wish someone would kill him!”. On the advice and directions of his mother, Lalthuama refused to pay tribute and supply labour to the colonial officials.

But, what irked the British the most was the fact that Lalthuama gave shelter to Pavunga and Hlawncheuva. Hlawncheuva’s name had emerged in the British records as a prominent Lushai murderer who was accused of murdering Lt. Stewart. Pavunga, on the other hand, had shot own one interpreter called Satinkhara who worked for the British. Both their cases were then under the investigation of Shakespear. The British now decided to impose a hefty fine on the mother-son duo for disobeying and challenging the colonial authority. When Lalthuama refused to comply with the Superintendent’s demand for labour and payment of fine, a suspicion arose in the British camps that the mother-son duo was attempting an uprising against the British together with their fellow villagers.

In August 1893, Capt. Shakespear and his men numbering more than 80 set off to subdue and subjugate the villages under the control of Ropuiliani and her son Lalthuama. They sent a message demanding 30 guns, 1 gayal, 10 pigs, 10 goats, 20 chickens, and 100 maunds of rice; and that the common villagers had to bring all these items to the Mat river where the British troops would be camping and waiting for food. Both mother and son assuredly did not want to comply with these demands. Rather than give what they had asked for, they preferred to declare war against the foreigners. They invited the Lals from the Northern Lushai Hills to help them in their fight. The war preparations began immediately thereafter. But, somewhere around March 1894, it accidentally reached the ears of Capt. Shakespear, much before the Lals of the North could make their appearance and chalk out the strategies of the war.

Shakespear now decided to terrorize the common village folks. The villages of Lalthuama and Ropuiliani were attacked in the middle of the night suddenly and unexpectedly. All the chiefs and chieftesses were taken captives and their guns and weapons seized. Ropuiliani and her son were arrested and imprisoned by the British Government on October 26, 1893 at Lunglei (the second-largest town in Mizoram after Aizawl). On April 8, 1894 they were deported from Lunglei to a British jail at a place called Rangamati, headquarters of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in present-day Bangladesh. In the prison, it is said that Ropuiliani refused to eat the food that was served by the British administrator. She never yielded to the British pressure of surrender and stood in defiance of the colonial authorities even after her detention.

Fearless till her Last Breath

In order to befit their ranks as chiefs, the British officials had proposed to appoint both mother and son as peons in the Chittagong jail with a monthly remuneration and some basic emoluments, which they strictly refused. But, the shock of being a prisoner of the British became too difficult for Ropuiliani to bear. Barely within a period of two years after her incarceration, she finally breathed her last in the same prison on January 3, 1895. She had been suffering from diarrhoea for a long time and was deprived of proper treatment in the jail. Ropuiliani was 86 years old when she passed away. Her body was allowed to be transported to her own home by her son Lalthuwama. The rest of her sons had already died in different battles by the time she was arrested. Lalthuwama was now set free and allowed to accompany his mother’s dead body. Ropuiliani was laid to rest in Ralvawng, her own village.

And so the chapter of the courageous Lushai chieftess, who had done her utmost to protect and defend her beloved land and country like a true patriot, and who resisted the British to the end of her life, came to a close. Ropuiliani’s struggle for freedom was located in a rough terrain of dense forests, hills and dales, valleys and rivers. The nature of this geographical landscape in itself was fraught with enormous logistic difficulties and dangers from wildlife and other natural calamities. But, it provided the much-needed backdrop to the struggles of Ropuiliani and her fellow men. They utilized the wisdom that they had of their natural habitat to their maximum possible advantage to check the movements of the enemy. They worked closely with the local chieftains, soldiers and ordinary citizens. After Ropuiliani’s death, it became easier for the British to subdue the remaining Lushai chiefs, many of whom were murdered.

The administration of the nine villages never came under the control of the natives or even the descendants of Ropuiliani. As written by a Mizo historian Sangkima, “Messages were dispatched to the neighbouring villages informing them to surrender their arms. The response was a rapid fear of further intimidation…the people also abandoned the idea of resistance although isolated outbreaks occurred here and there”. The downfall and death of our very own daring Ropuiliani thus witnessed the beginning of total British paramountcy in the Lushai Hills. This was subsequently followed by the annexation of the entire Lushai Hills area by the British in 1895, when it was formally declared a part of British India. On April 1, 1898, Lushai Hills district with Aizawl as its headquarters was created and it became a part of the British province of Assam.

Ropuiliani’s movement was a short-lived one, but its significance can be understood from the fact that it was a broad and all-encompassing expression of the people’s angst against the injustices of the colonial rule. They protested against it in whatever way they could, inventing their own rituals and symbols of struggle. In the post-colonial and contemporary rethinking of the history of resistance against colonialism in the Lushai Hills, Ropuiliani has become an inspiring idol of bravery and patriotism. A few other women like Pi Buki, Dabilhi, Laltheri, Pawibawia Nu, Pakuma Rani, Rothangpuii, Thangpuii, etc. also equally struggled against colonialism. But, they remain comparatively unknown and unexplored. Exploring, revisiting and documenting about them is an utmost necessity.

References:

1. Gupta, Ramanika & Beniwal, Anup. (2007). Tribal Contemporary Issues: Appraisal and Intervention. Concept Publishing Company, New Delhi.

2. Hluna, J.V. (1990). Ropuiliani: Her Role in the Freedom Struggle in Mizoram. Proceedings of NEIHA, Eleventh Session, Imphal, pp. 193-199.

3. L. Khimun (ed). Socio-Cultural and Spiritual Traditions of Northeast Bharat. Heritage Foundation, Guwahati, Assam, 2012.

4. (2009). Changing Status of Women in North-Eastern States: Felicitation Volume in Honour of Prof. C. Lalkima. Mittal Publications, New Delhi.

5. Lalthangliana, B. (2005). Culture and Folkore of Mizoram. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

6. Zorema, J. (2007). Indirect Rule in Mizoram 1890-1954. Mittal Publications, New Delhi.

Acknowledgement: A sincere note of thanks to Kheminda, Diana, Desana, and Hangjet who have always accompanied me to different places of Uttar-Purba Bharat in my field travails, and without whose support gathering information for writing this piece would never have been possible.

Featured image courtesy: Google and Twitter (@mizozeitgeist).