24 Major Famines between 1850 to 1899! How 1 Spawned a University?

Without the River Ganges there would have been no canal of that name, and, without the canal, no college at Roorkee.

Till the medieval era, India never knew famines. How could it be? It was the only country in the world that raised three crops yearly. The earliest known famine was in Kalinga in 269 BCE but was wholly war-related. In the medieval era, the Islamic invasions frequently spawned famines that killed lakhs of people. However, after the arrival of the British, it became a decennial problem as from 1850 to 1899, 24 major famines occurred, the most in Indian history. Some even say it was deliberately engineered (or doctored?) by them to keep Indians under their feet.

One such was the Agra famine of 1837 in which 8 lakh people died due to starvation and violence. The situation was such that hungry, angry people resorted to crime to loot warehouses and homes of the rich. East India Company, however, felt no pangs of shame. Yet, its pocket was pinched when the revenue reduced drastically and its share price in the London stock market went down dramatically. It even had to spend Rs 1 crore on relief work on beastly people. Perturbed by this loss, Governor-General Auckland felt a canal is needed to irrigate the Ganga-Yamuna doab to prevent the crops from failing in case of monsoon failure. A talented British engineer was assigned the job of making such a canal that would run through the Agra region. He was Proby Thomas Cautley.

He spent six months walking and cycling across the region, measuring everything personally. He was optimistic that a 500-kilometer canal could be built but encountered several challenges and objections to his project, most of which were financial in nature. This project was finally approved in 1841, and the construction began in April 1842. However, new Governor-General Ellenborough, unsure of its engineering, stopped the cash flow. Cautley persisted and could persuade the Company to sponsor it but was granted only Rs 2 lakh a year which was highly inadequate. Only after the appointment of a new Governor-General, Lord Hardinge, in 1844, did official excitement and finances return to the Ganges canal project. However, this stress took a heavy toll on Cautley’s health, forcing him to take a sabbatical in London. Still, he did not waste time there and kept studying hydraulic engineering. He also visited Italy which had ancient aqueducts of the Roman era. The Project really took wings when Dalhousie became the Governor-General in 1848.

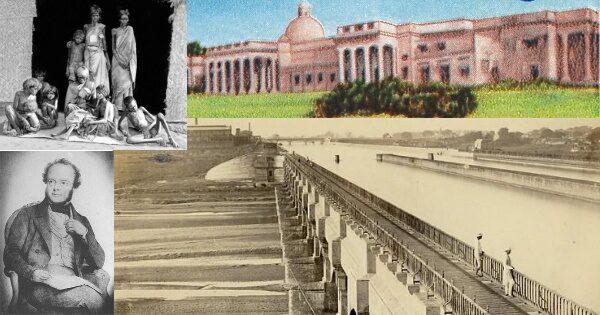

Back in India, Cautley even had to make his own bricks, kiln, and mortar initially, but this could not go on forever. He needed assistance to complete the project on time, and for this purpose, Lieutenant Baird Smith of the Bengal Engineers was made in-charge of training students in civil engineering for the position of sub-assistant executive engineer at Saharanpur. In 1846, 20 pupils were allowed to this class, which was held within a tent. Almost immediately, it was found inadequate and a need was felt for better infrastructure. James Thomason, the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-Western Provinces (which included Roorkee at the time), intervened and an engineering college was established in Roorkee in 1847 to assist on the Ganges Canal. It thus ended up spawning the first engineering college in India.

In those times, Roorkee was a mofussil town on the Delhi-Haridwar highway. The name ‘Roorkee’ was derived from Ruri, the wife of a local Rajput chief. The twin projects of the canal and college catapulted it on the world stage. Thomason made the following submission to the Governor-General for choosing Roorkee as the location on September 23, 1847:

The establishments now forming at Roorkee, near the Solani Aqueduct on the Ganges Canal, afford peculiar facilities for instructing Civil Engineers. There are large workshops and most important structures in course of formation. There are also a library and a model room. Above all, a number of scientific and experienced officers are constantly assembled on the spot or occasionally resorting thither. These officers, however, all have their appropriate and engrossing duties to perform and cannot give time for that careful and systematic instruction, which is necessary for the formation of an expert Civil Engineer. On these accounts the Lieutenant-Governor would propose the establishment at Roorkee of an institution for the education of Civil Engineers, which should be under the direction of the Local Government in the Education department.

Lieutenant R Maclagan was appointed college principal on October 19, 1847. The following month, a headmaster, an architectural drawing master, and two Indian teachers joined him. However, the first student admitted to the institute was on January 1, 1848. Those 20 students were also transferred from Saharanpur to Roorkee. Even in Roorkee, classes continued to run in the tents.

The college initially had three departments. The first department required ability in reading and writing English as well as an understanding of Geometry, Algebra, Mensuration, Plane and Spherical Trigonometry, Conic Sections, and Mechanics. The upper age limit was 22, and the department had a maximum capacity of 8 candidates.

The second department was only for non-commissioned officers and troops from Europe, a hint of probable racism. Before admission, they were supposed to pass an elementary reading, writing, simple drawing, and maths test. The total seats were ten each year. These soldiers were trained to be Public Works Department supervisors (PWD), a brainchild of Lord Dalhousie. They were also taught local languages to converse with Indian labour.

The third department was reserved for young Indians and provided only surveying, levelling, and drawing training. Arithmetic knowledge was required, as was the ability to read and write Urdu. Admissions were limited to a maximum of 16 pupils. Annual examinations were administered for all courses, and entrance tests began in 1857.

On the other hand, the work at the canal commenced, but at the very start, Cautley ran into an unexpected problem.

The priests vehemently opposed the project in Haridwar, who feared that the sacred river Ganges would be sullied. Surprised by the outburst of a new stakeholder, Cautley had to devise a novel strategy of appeasing them by promising to create a breach in the dam through which the holy river could flow freely. He also mollified them by repairing bathing ghats along the river and inaugurated the dam by invoking Lord Ganesha. The dam’s construction had seemingly insurmountable problems as various tributaries were crisscrossing the canal. Cautley had to build an aqueduct to carry the canal for half a kilometre at Roorkee since the land sloped down rapidly. As a result, the canal at Roorkee is 25 metres higher than the original river. The canal’s main channel was 560 km long and cost Rs 1.5 crore when it was formally inaugurated on April 8, 1854. Its branches were 492 km long, and its many tributaries were almost 4,800 km long, a mind-boggling feat to achieve in just 12 years. It had the potential to irrigate over 5,000 villages with 3,100 Sq km area. It began its voyage in Haridwar and, after splitting at Aligarh, joins the Ganges river in Kanpur and the Yamuna river in Etawah. It also had the highest discharge of any irrigation canal in the world when it was finished. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, instrumental in stealing Kohinoor, the Diamond, from India, inaugurated it.

According to historian Ian Stone:

It was the largest canal ever attempted in the world, five times greater in its length than all the main irrigation lines of Lombardy and Egypt put together, and longer by a third than even the largest USA navigation canal, the Pennsylvania Canal.

Along the canal, there are five massive lions, two at Roorkee, two at Mehwar village, 2.5 Kms from Roorkee and the fifth one at nearby Sher Kothi, the area where Cautley once lived. A significant amount of landfilling was necessary for the canal to maintain the requisite level between Roorkee town and Mehwar. The two lions at each point were constructed to signal that the canal in the filled-in segment is in a danger zone, and the lions are there to protect the area. The fifth lion was made first as a model, and once it was perfected and finalised in design, the four other sculptures around the canal were built.

The five sculptures depict royal lions seated yet attentive, paws extended out and head raised high, secure in his majesty and might but displaying no fear or wrath. The lion was chosen to represent the spirit of the college. While the design of the logo altered a few times throughout the years, the lion remained a vital feature of it and can still be seen in numerous places. The lions are said to be structurally identical to those at Trafalgar Square in London. They are composed of black granite, but the lions in Roorkee are made of bricks and lime mortar since cement was not available at the time, but their size and form are identical to those in London.

Contrary to the perception, the first railway line in India was opened on December 22, 1851, from Roorkee to Piran Kaliyar, ten kilometres away, to deliver the clay needed to build the aqueduct over the Ganga Canal. It was named the Solani Aqueduct Railway as it was to be built over the River Solani. Till now, the supplies were hauled by men and animals, both having their own whims and fancies. During the previous few years, Cautley had seen four labour strikes. Piran Kaliyar had a large quantity of clay to make the aqueduct near Roorkee and he was searching for a cheaper, more reliable and faster means to transport it. The train’s engine was brought in from England the same year. It was called Thompson after the project’s executive engineer, who designed the installation of the railway system in the region. It was “a tiny but compact machine, with both engine and tender on one frame and capable of drawing 200 tonnes on the level at four miles per hour.” Initially, two bogies were coupled to the engine, each capable of carrying between 180 and 200 tonnes of cargo. It covered the distance in 38 minutes at a speed of approximately four miles per hour. The engine itself ran for around nine months until catching fire in 1852. The train that ran between Mumbai and Thane in 1853 was the first commercial one.

In the 19th century, the British were proud of the Solani aqueduct, where the canal stretches 2.25 miles above the land and the seasonal Solani River. It was an exceptional structure with the water bridge 172 feet wide and 24 feet tall, and two lions stood at either end to mark the start of the canal’s irrigation section. One observer noted in 1887 that it was “the most stupendous monument of that kind yet constructed.” Engineers from all over the world came to see the place where the canal crossed the river.

In 1854, after the completion of the canal and Thomason’s death, it was renamed Thomason College of Civil Engineering by Cautley. There is a particular controversy regarding it being the first such college. The British established another engineering institution, the School of Survey at Guindy in Chennai, in May 1794. However, it was not until 1859 that it became Civil Engineering College under Madras University, hence the first college tag is happily retained by us.

In 1857, The first war of Independence started on 10th May 1857 in the neighbouring city of Meerut and Roorkee was not left untouched by the watershed event. Sensing the danger to the British, their women and children were put in the basement of the college workshops. The wives of Lieutenant R Maclagan, the first principal, and Lieutenant Baird Smith, the first teacher, were pregnant and were due for delivery at any time. On the night of 13th May, a barrack occupied by British soldiers was set on fire by the rebels but no damage was done. They were then transferred to the fortified enclosure of the Canal Foundry Workshops (present Government workshop Roorkee (GWR)). In these foundry workshops, they were blessed with children. A plaque in this regard has been put up outside the workshop.

Till 1852, the classes continued to run in the tents, but the need was felt for better infrastructure. Cautley scouted for the location and competent person to build the campus. His eyes fell on Lieutenant George Price who was also working on the Ganga canal. He then became its architect and builder and despite working full time there, he managed to take time out for his passion. He designed it in the Renaissance style with huge doors, high pillars and long corridors, a subtle reminder of the institute’s brilliant history. Its magnificence underscores the institute’s global significance in technical education and research. The majestic structure, completed in 1856, gazes across the plains to the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas. Several additions were made to it along the way. For over a century, the quadrangle of the building contained the educational facilities as well as the administration. The beautiful vast green grounds in front provide the necessary foil, creating an unforgettable impact on the beholders. The clock at the dome is a four-faced, eight-day clock, designed by MacCabe. In 2013, it was rechristened as James Thomason Building. It now functions only as an administrative office as every department has its own building. The institute is fully residential as multiple hostels exist. One hostel is named after Cautley, where I had the privilege to stay during 1987-88.

Another interesting feature is its convocation hall. During World War II, from 1939 to 1945, it served as a hangar to park the military planes and helicopters. Since then, it is called hangar. The most visible aspect of the institute is its 15-storey high communication tower which can be seen from a distance of 25 kms. It was designed by Aditya Kamal in the late 1970s who was the HOD of the electronics department. In 1949, The college was elevated to a university and, in 2001, converted into an IIT. The last up-gradation created an existential dilemma for oldies as to whether they should now consider themselves IITians or not.

All along, the college kept producing stalwarts. The foremost is Sir Ganga Ram of the 1873 batch, a leading philanthropist, agriculturist, and civil engineer, who supervised the construction of several prominent structures in Punjab. He was commonly referred to as the Father of modern Lahore. Friedrich Oscar Oertel was another distinguished student of the 1883 batch who changed the direction of Indian archaeology. As a PWD engineer, while laying a road, he discovered the archaeological site of Sarnath in December 1904. A few months later, on 15th March 1905, he unearthed the Lion Capital on an Ashokan pillar, which would later become India’s national emblem. Impressed by his dedication to restoring Indian heritage, Viceroy Curzon tasked him with restoring Diwan-i-Aam and Jahangiri Mahal in the Agra Fort and reconstructing the four minarets of the south gateway of the Akbar tomb in Sikandra in 1905–1906 and the compound of the Taj Mahal. He came across the sculptures of Yoginis in Chitrakoot and documented them in detail.

AN Khosla of the 1916 batch supervised the construction of The Bhakra Nangal dam in Himachal Pradesh. Kanwar Sen of the 1927 batch was instrumental in setting up the prestigious projects from the Damodar Valley to the Rajasthan Canal, from Hirakud Dam to the Narmada River Project. Another stalwart GD Agarwal of the 1953 batch, went on the fast to stop environmentally unfriendly projects on the Ganges and died in 2018 after 111 days of starvation. He was against the river being used as a vast water machine, with the entire basin being transformed into a workshop of man-made experience.

One more prominent engineer was Raja Deen Dayal of the 1866 batch. In the late 1840s, the camera was invented in Europe, prompting the British to use it as a surveillance tool and one more piece of equipment for conquest. After graduation, Raja chanced upon a camera and instantly fell in love with photography. Soon he became the most famous photographer in India and went on to click various royalties of Indore, Hyderabad, Baroda, Prince and Princess of Wales and even Viceroy of India. However, he did not let his talent go to waste in such bombast and proceeded to click every temple and palace in Central India. Among the distinguished alumni, two received Padma Vibhushan, the second-highest civilian award in India, two received Padma Bhushan and one got Padma Shri. The institute also produced numerous CEOs, IAS officers and world-class scientists. However, it is not like every student went on to become a world-changer. Some are indeed like me also who are content to remain lesser mortals.

At the other end of the spectrum, there was one Chaudhry Niaz Ali Khan of the 1900 batch, who went on to become a prominent member of the Muslim League and was instrumental in the partition of India.

In 1997, a stamp was dedicated to the 150th anniversary of the University of Roorkee. Even after 170 years of its establishment, it continues to be in the top institutes of the world. It is the 6th best engineering college in India, 90th in Asia and among the top 500 in the world.

The rest of India remained plagued with manmade famines till its independence while the canal indeed went on to create wealth for its people with no severe famine being encountered in the region. Let’s pay homage to all the victims of the Agra famine to whom we owe our illustrious careers. Om Shanti.

Sources:

1. K V Mital, The History of Thomason College of Engineering

2. Colonel Sir Proby T Cautley, Report on the Ganges Canal Works, From the commencement until the opening of the Canal in 1854

Swift Horses Sharp Swords authored by Amit Agarwal.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely of the author. My India My Glory does not assume any responsibility for the validity or information or images shared in this article by the author.

Featured image sourced from Google.