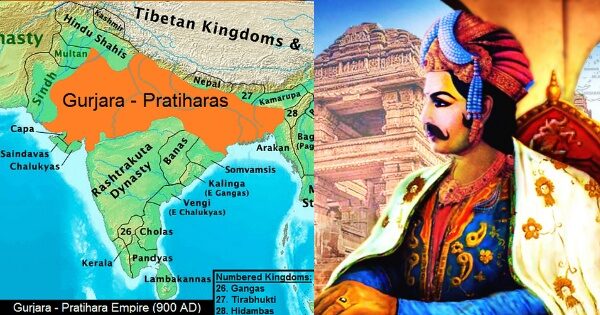

How Gurjara Pratiharas Resisted Islamic Invasions in 8th-10th Centuries

As we get ready to celebrate the birth anniversary of Gurjara Pratihara Samrat Mihir Bhoja on 9th Sep 2021, one question that seeks an answer from our historians is why have Indian history textbooks failed to reflect the glorious history of the Gurjara Pratiharas? Why is it that this is not taught to our students when there is undisputable and conclusive evidence about the Arabs intruding into the Indian territories through military expeditions and how the Gurjars stood as a bulwark of defence. Why do our history textbooks don’t describe how the Gurjara Pratiharas offered stiff resistance against the Arab invaders and stood against the vanguard of Islam even as Spain, Portugal, SicIly, and Malta fell to the Arabs swords? Our academic curriculum do not examine the contribution of Gurjara Pratiharas to the polity, society and culture of India.

Ask an average student about the Gurjara Pratiharas and the Gurjara Pratihara Samrat Mihir Bhoja; a blank response may be expected. The only explanation for this blurring of India’s past is the deliberate distortion of history first by the western historians and scholars and then by the leftist Nehruvian intellectuals, oblivious of India’s true culture and history. There is an urgent need to objectively and comprehensively study the Gurjara Pratihara period and correct distortions and present facts about Indian history in the right context and perspective. It is essential that we develop a truthful narrative of our history which is vital for our national awakening and progress.

The Gurjara Pratihara dynasty was one of the longest-reigning dynasties of India. The rise of Gurjara Pratiharas was a momentous event in the political horizon of India in the 8th century which left its indelible mark for the next 400 years of Indian history. Various ruling dynasties like the Tomars of Delhi, Chouhans of Sakambhari, Parmars of Dhar, Chap, Chalukyas and Solankis of Gujarat who all subsequently launched a glorious chapter of their own in Indian history apparently started as feudatories of Gurjara Pratiharas and were linked to them closely through military and matrimonial ties. Famed in later times for their military reputation, these Gurjara ruling lineages of North India left their mark through diverse tangible and intangible ways on the consciousness of posterity.

The need to know about the Gurjara Pratiharas leads us to the question of their origin. For a long time the theory was held that Gurjars were foreigners who entered India along with or about the same time as Huns and became rapidly Hinduised. The historical research clearly shows that there is no evidence for Gurjars living outside. Well-known historians Dr. BN Puri and Upinder Singh have put forward the view that there is not an iota of positive evidence that the Gurjara Pratiharasand the present group of Gurjaras living in various states of northern India who can be related to ancient Gurjars represent any non Indian group of peoples.

The earliest evidence for the Gurjaras can be traced to the Panchatantra, Yog-Vashisht, Bhavishya Puran, Skanda Puran, Narada Puran. We get references to Gurjars from Bana’s Harsh Charita, Kalhan’s Rajatarangini and the literary works of Adi Kavi Pampa called Vikramarjun Vijaya. There are number of references to the Gurjars both in Gurjara Pratihara and non-Gurjara Pratihara inscriptions of the time.

There is an interesting reference to not only to the origin of the Gurjara Pratiharas from the Gurjar caste but also to the fields cultivated by the Gurjara cultivators in Rajor inscription of Mathandeva. The contemporary Arabs record of merchant Sulaiman and the works of Muslim historians like Ibn-khurdabh, Al-biludri and Al-Idris talk about the Gurjara kings and Gurjara kingdom.

Some scholars are of the opinion that Gurjara was primarily the name of the country and not people. The great grammarian Panini in his book Ashtaadhayi says countries get their name from the fame of the Kshatriya kulas and most historians including Dr. Upinder Singh agree with this view. The Gurjars as an ethnic group spread over different parts of India and lent their names to place names like Gurjaratra – modern state of Gujrat, Gujargarh in the northern part of former Gwalior, Gujarat another name of district Saharanpur, Gujranwala, Gujrat, and Gujar Khan in western Punjab, all marking the settlements of Gurjaras in ancient India.

Gurjars were ancient Kshatriyas, which is testified by their copperplates which have an emblem of the sun. In their seals too, the sun is depicted. Poet Raj Shekhar in his plays style Gurjara rulers as Raghukultilak, Raghukul-muktamani and Raghukul-gramini all pointing to their Suryavanshi Kshatriya lineage. The Gwalior prashsti composed by Baladitya traces the origin of the Gurjara Pratiharas to Lakshman. In that family was born Nagabhatta who appeared in the image of sage Narayan and was of pure Kshatriya origin.

The most formidable of Arab invasions was in 725 A.D. when the Arab forces overran Cutch, Kathiawar, Northern Gujarat and probably advanced as far Malwa in Northern India. The chief of Gurjara Pratihara clan offered resistance. He was Nagabhatta, the ruler of Avanti in the first half of the 8th century. Nagabhatta incorporated all smaller principalities after his great victory over the Arabs and laid the foundation of a mighty empire. It reached its zenith of power and glory until the period of Gurjara Pratihara Samrat Mihir Bhoja, son of Rambhadra and Appa Devi. He had inherited a crippled kingdom under adverse situation. At his death he left a consolidated empire to be enjoyed by his descendants for a couple of centuries. The Arabs’ storm had lulled and the strong centralised power and authority wielded by Bhoja immuned India stopped foreign inroads for a long time.

Arab historian Sulaiman records ‘the king maintains numerous forces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry. He is unfriendly to the Arabs still he acknowledges that the king of Arab is the greatest of kings. Amongst the princes of India, there is no greater foe to the Mohammedan faith than he. He has got riches and his camels and horses are numerous. Exchanges are carried on in his state with silver and gold and there are said to be mines (of these metals) in the country. There is no country in India more safe from robbers.”

The Muslims whose main purpose was the expansion of Islam through sword were met with a changed social outlook under the Gurjara Pratiharas which reclaimed those who were lost to the alien faith. The Devala Samriti opens with a question put to Devala how Brahmans and members of other varnas carried of by Malechhas to be restored to the caste. The advice given by Devala constitutes a neat and tiny composition not exceeding 90 verses. The confirmation of this social phenomenon is available from the accounts of the Arabs historians.

The dramas of Rajshekhar give us an insight into the social life of the period marked by prosperity and high social status accorded to women. This is reflected by Karpur Manjari, the play written and staged by poet Rajshekhar to please his wife Avantisundri, a Chouhan princess of taste and accomplishment. Women were a happy class, conscious of their marital obligations and responsibilities. They enjoyed playing musical instruments, painting, dancing and singing with no veil concealing them. Ordinary women were equally interested in their pleasures and pastimes reflected by references to singing wives of herdsmen in literature. Bands of women who lived on arms reflect on free-spirited and brave women.

In the last few decades, our knowledge about the Gurjara Pratihara artistic and architectural heritage has increased many folds due to excavations, restoration and renovation undertaken by Archaeological Survey of India. The iconographic sculptural and architectural attainments of the Gurjara Pratihara period are truly mesmerizing. The Purta dharma which consisted of building temples, tanks and undertaking work of charity was emphasized in the Purans and Smritis during the Gurjara Pratihara period. Large number of temples were constructed by the Gurjara Pratiharas.

Mihir Bhoja was a great patron of temple architecture, which is revealed by the number of temples found at various sites in northern India. Architectural evidence shows the growing importance of temples in the socio-religious life of the people. Staging of dance dramas, reciting of Purans and other religious texts, celebrations of the festivals on the temple premises had become important during this period. The Chatur Bhuj temple of Gwalior has two engraved inscriptions dated in V.S 932 (A.D. 875) and V.S 933 (A.D 876). In this Vishnu temple, Mihir Bhoja has been mentioned with his appellation of Shrimadhadivaraha. In the temple, Vishnu is represented in his ten avatars. In the temple, scenes of Krishna Leela are depicted i.e. arrival of the newly born child in Gokul, Putna vadh, stealing of butter, Govardhan dharna, and musical and dancing scenes. The Krishan Leela scenes were very popular under the Gurjara Pratiharas as these are depicted even in the Jain temples at Osian indicating that the theme had widespread appeal irrespective of any sectarian consideration.

The Pehoa inscription of A.D. 882 of the reign of Mihir Bhoja records the donee temples at Kannauj, Bhojpur and Pehoa though none of these temples is now available due to their complete devastation by iconoclast zealots. The records nonetheless point out the prolific temple building activity under Mihir Bhoja. Gurjara Pratiharas seem to have earned lasting fame in the temples of Bateshwar and Naresar in the Morena district of the Gwalior/ Gurjargarh region. About 2 kms from Padhavli, district Morena lies the Bateshwar valley where the remains of a large number of temples located in various states of preservation are lying over a large area. These temples at Bateshwar valley may be dated to the last quarter of the 8th century to the 9th century of the Gurjara Pratihara period. In these temples of Bateshwar and Naresar, we see interrelationships and interactions between various fields of arts, sculptures, dance and narration of stories. Temples of Bateshwar vividly narrate the stories from the Purans and Epics in sculptures. The most prominent temple is Bhuteshwar. The temple is still under worship and is dedicated to Lord Shiva. A large number of images of Parvati, Ganesha and Kartikeya clearly show it to be the temples dedicated to Shaiva sect.

From the temple site of Bhuteshwar, we have beautiful images of dancing Ganesha which are now preserved in the Gwalior museum. The group of Naresar temples are situated about 25 km northeast of Gwalior in Naresar valley. The most interesting and common feature of these temple sites is the location of the water tank which still provides water in the area. These tanks make the temple sites of Bateshwar and Naresar very attractive, creating a divine scenic aura as also an atmosphere of purity and spirituality. It is water that sustains life, the first principle of fertility and life. The archaeological evidence of temple tanks leave no doubt about the fundamental importance accorded to water by the Gurjara Pratiharas. The tanks with flowering lotuses, beautiful hills covered with forest and dancing peacocks in these temples are all sources of joy and inspiration to the local communities and tourists visiting them.

The inscription at Naresar dated Samvat 1329 (A.D.1272) has immortalized Gurjara Pratihara Samrat Mihir Bhoja in the memory of people. Even after 400 years of his death, Mihir Bhoja was recognized by the writer of this inscription as the ideal and liberal king of the past. Let us pledge to revive the glorious past of India under Gurjara Pratihara Samrat Mihir Bhoja in the consciousness of people. That will be true education and with it, a true spirit of national achievement and pride will be awakened.

Ref:

1. The History of the Gurjara Pratiharas, Dr. Baij Nath Puri.

2. Political History and Administration cir AD 750- 1300, Ed. Dilip K. Chakrabarti and Makhan Lal.

3. Ancient India, R.C. Majumdar.

4. The Dynastic History of Northern India Vol 1 and 2, H.C. Ray.

5. The Ancient Geography of India, Alexander Cunningham.

6. Prachin Aivam Purva Madhyakalin Bharat ka Itihas, Upinder Singh.

7. Temples of Pratihara Period in Central India, R.D. Trivedi.

8. Art and Icon, Devangana Desai.

9. Karpurmanjari, Rajshekhar.

Featured image courtesy: Facebook and World History Encyclopedia.