What if Shaikh Paltu had Helped Mangal Panday instead of British?

Mangal Pandey was a sepoy in the 34th Bengal Native Infantry, Barrackpore, Bengal. He hated the British though he served under their command. He 19th of July, in 1827 at Nagwa village in Uttar Pradesh.He was hanged to death by the British in Barrackpore, Bengal. He was one of the earliest freedom fighters who triggered the ‘War of Independence of 1857’.

He regularly motivated fellow sepoys to rise in rebellion. In the early months of 1857, news about bullet cartridge used in the Enfield P-53 rifle (which was to be introduced in BNI) being smeared/greased with cow’s/pig’s fat, which needed to be bitten at one end before use, reached the sepoys’ ears. This was against the religious faith of both Hindus and Muslims.

About the greased cartridges and about the source of the war of independence of 1857-58, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar opines thus in The Indian War of Independence 1857, “The clever English administrators had so little information about the source of the movement, even after the tremendous revolutionary upheaval all over Hindusthan, that, even a year after open mutiny had broken out, most of them still persisted innocently in the belief that it was due to the greased cartridges ! The English historians are now beginning to understand that the cartridges were only an incident and they themselves now admit that it was the holy passion of love of their country and religion that inspired the heroes of the war of 1857.”

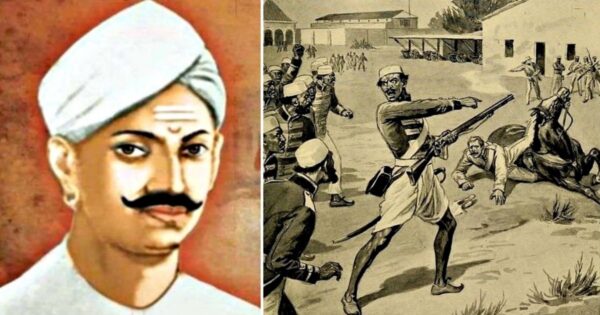

On 29 March 1857, Mangal Pandey, armed with a loaded musket and walking in front of the guard room, was all ready to shoot at the British officer that he would first see. At the same time, he asked his fellow Indian sepoys to be ready with their rifles too. As decided Mangal Pandey saw Lieutenant Baugh, Adjutant of the BNI. He immediately fired at him. Baugh was galloping on a horse; the bullet thus missed him and instead hit his horse. Baugh fell. Pandey had already killed a British officer by then.

Savarkar describes the event thus in The Indian War of Independence 1857, “The sword of Mangal Panday positively refused to rest in its scabbard. The 34th regiment wanted to leave the Company’s service quite as much as the 19th. Hence all patriots thought it was best that the Company itself disbanded the 19th….. The idea that his brethren were going to be insulted before him fired Mangal Panday’s heart, and he began to insist that his own regiment should rise on that very day. When he heard that the leaders of the Organisation would not consent to his plan, the young man’s spirit became uncontrollable, and he at once snatched and loaded his gun, and jumped on the parade-ground, shouting, ‘Rise! Ye brethren, rise! Why do you hold back, brethren? Come, and rise! I bind you by the oath of your religion! Come, let us rise and attack the treacherous enemies for the sake of our freedom.’ With such words, he called upon his fellow-soldiers to follow him. When Sergeant Major Hughson saw this, he ordered the Sepoys to arrest Mangal Panday. But the traitor-Sepoys whom the English had been used to count upon upto now were nowhere to be found. Not only did no Sepoy move to arrest Panday at the orders of the officer, but a bullet from Panday killed the officer, and his corpse rolled on the ground! Just at this time. Lieutenant Baugh came upon the scene…”

Mangal Pandey rushed towards Baugh and attacked him with his talwar before the latter could draw his sword. The brave freedom fighter brought him to the ground and was about to hit him when a fellow sepoy – Shaikh Paltu intervened and saved Baugh’s life. No one stopped Panday. Even upon the orders of the British no other Indian sepoy stopped him. Only Shaikh Paltu came to the aid of the British otherwise death of several British officers was certain at the hands of Mangal Panday.

To quote from A History of the Indian Mutiny by T Rice Holmes (fifth edition published in 1904), “One man only, a Mahomedan named Shaikh Paltu, came to help the struggling Europeans, and held the mutineer while they escaped. Meanwhile, other European officers were hurrying to the spot. One of them, Colonel Wheler of the 34th, ordered the guard to seize the mutineer: but no one obeyed him.”

British Sergeant Major Hewson ordered quarter guard Ishwari Prasad to arrest Mangal Pandey, but he did not. By then Mangal Pandey fired another shot at Lieutenant Baugh and injured him. Hewson intervened but Pandey knocked him down with his musket.

Shaikh Paltu, who was still trying to hold back Pandey, seizing him around the waist, ordered his followers to join him and save the British officers. By then, General Hearsey arrived at the scene and arrested Mangal Pandey. Pandey tried to end his life to avoid falling in the clutches of the British. At a lightning’s pace he put the muzzle of the musket to his chest, pressed the trigger with his foot, and discharged it right to his chest. He started bleeding profusely, but did not die.

Mangal Pandey was then tried in court. Despite being subjected to tortures, he did not utter the name of fellow freedom fighters who conspired against the British. Four hangmen were brought from Calcutta for the execution of Mangal Panday. He was carried to the scaffold on the morning of the 8th April 1857 at Barrackpore, surrounded by soldiers. As he ascended the scaffold, he repeated that he would never mention the names of any of the conspirators. The noose dropped. Panday was only 30 years old then.

Ishwari Prasad was hanged by British few days later. Shaikh Paltu, for his loyalty to the British and for helping save the lives of British officers, was promoted from his post of sepoy to havaldar and was rewarded. The 34th Bengal Native Infantry was disarmed and disbanded after six weeks, i.e. on 6th May.

Imagine if Shaikh Paltu had not helped the British and instead if he had supported Mangal Pandey! Imagine if all the sepoys together attacked the British then like Mangal Pandey did!

The right featured image, sourced from Wikimedia, is a representation of Mangal Pandey attacking a British lieutenant immediately before Shaikh Paltu’s intercession – featured in Edward Gilbert’s book ‘Heroes of the Indian Mutiny; Stories of Heroic Deeds’. The left image is sourced from Google.