Sakti Worship in North-East India: Historical, Cultural Perspective

Historically speaking, the region of Kamarupa (present-day Assam) has always been well-known as the original centre for the followers of the Sakta panth of Hindu Dharma. Located on the Nilachal hill on the south bank of the Brahmaputra in Guwahati, Assam, the Ma Kamakhya Saktipeeth is the primary seat of Sakti worship for all Sakta sadhakas. The present-day structure of the Kamakhya temple was re-built by Koch King Naranarayan after the original one was destroyed by Muslim invaders led by Kalapahar, a General of the Afghan ruler of Bengal Sulaiman Kareni. The entrance to the temple was later constructed by the Ahoms.

The garbhagriha at Kamakhya houses not a murti, but a rock shaped like a vulva from which red-coloured water flows out continuously at all times, in all seasons. The rites and rituals that can be observed at several Saktipeeths of Assam and the North-East including Kamakhya, are intense and traditional, rooted in the Tantric paddhati of worship. A few historic temples such as the Burha Goxai Thaan at Howli, Mohanpur in Darrang district of Lower Assam, the Ugratara Devalaya in Guwahati, and the Bilbeswar Devalaya at Belsor, Nalbari have preserved their timeless tradition of Sakti worship, i.e. celebrating Durga Puja in their own unique and distinctive ways.

It was around circa 1615 that Koch King Dharma Narayan is said to have shifted the capital of his Kingdom from Kerkeriya in the foothills of Bhutan to Mohanpur, the then capital of present-day Darrang district. The Burha Goxai temple is surrounded by an earthen fort (Garh) with two temple ponds located amidst the then residential settlement of the Koch royal family of Darrang. The locals of the area believe that King Dharma Narayan had first begun Sakti worship – celebrations of Durga Puja, in the premises of the Burha Goxai temple since circa 1620.

Devotees performing Vaishnavite naam-kirtan in the Durga Puja held at the Burha Goxai temple

The temple is believed to have a history dating back approximately 400 years and back, with some artefacts and shrines perhaps being even older. Currently, the temple houses a Yonipeeth (known as the Linga among the locals), several small murtis, utensils used during Durga Puja events, and temple manuscripts. These artefacts and structures provide a glimpse into the rich cultural heritage and religious practices associated with the temple since antiquity. Durga Puja is the main festival held at the temple. Other important festivals celebrated here include Kali Puja, Sivaratri, Jagaddhatri Puja, Annapurna Puja, and Ma Manasa Puja.

In the Ugratara Devalaya of Guwahati, it is said that Devi Ugratara resides in the form of three different avatars – Chamundi, Dakshina Kali, and Neel Saraswati. Jor Pukhuri, the famous tank situated towards the West of Ugratara attracts hordes of visitors everyday, feeding the swans who have now almost attained a near cult stature. Thousands of devotees throng to be a part of the age-old tradition of buffalo sacrifice at the Bilbeswar Devalaya in Nalbari on the day of Mahanavami during the annual Durga Puja festivities. Besides Bilbeswar, the 530-year old Durga Puja at Barnardi village in Nalbari is one of the oldest in Assam.

Several local elements have influenced the religious rituals in the temples of the North-East since antiquity. E.g. the usage of meat and fish as prasadam in the Saktipeeths here often intrigues people from other parts of the country. Bali pratha (animal sacrifice) is a distinctive anthropological and geographical feature in these temples, influenced by the lifestyles, food habits and traditional religious belief systems of several hundreds of vanavasi communities residing in this part of Bharat. The matriarchal family system is still in prevalence among many of these communities residing in the Brahmaputra Valley, besides the Khasis, Garos, and Jayantias of Meghalaya.

It is thus a religious custom among several such communities, such as Jaintias, Bodos and Koch-Rajbongshis of Assam, etc. to worship Sakti. A popular belief is that the Khasis and the Jaintias were the original sadhakas of Ma Kamakhya. A significant section of the Jaintias worships this Sakti as Jayanteswari Devi in the 600-year old Durga temple situated at Nartiang village of Jowai in the West Jaintia hills of Meghalaya. Another belief is that the present-day Kamakhya Saktipeeth in the Nilachal hills could possibly have been an ancient sacrificial site of the Khasis. Similar to Kamakhya, there is no murti of the Devi in the Durga temple at Nartiang as well.

Sakti Worship in Meghalaya

As mentioned above, the Jaintias, Khasis, and Garos reckon their descent through the female line. The Khasis and the Jaintias believe that the world is ruled by the supreme Goddess called Ka Blai Synshar (Ka meaning ‘She’). Their indigenous religion is known as Ka Niam. With the growing popularity of Christianity, the suffix Tre, meaning ‘original’, has been added by the non-Christian population among them who take pride in themselves as the followers of the Niam faith system. Hence, presently, it is known as Ka Niam-Tre or simply Niam-Tre or Niam-Khasi (meaning ‘original religion’).

Nartiang Durga temple

The term Jaintia came to be used only after the area came under the British rule in the year 1835. This was done in order to differentiate it from the plains areas of the old Jaintia kingdom, the capital of which was Jaintiapur situated in the Jaintia Parganas of present-day Bangladesh. A popular local belief prevalent in the region is that the origins of the word Jaintia may be traced to Jaiyanti Devi or Jayantesvari (believed to be one of the ugra swaroopas of Devi). Sakti worship was prevalent amongst the royal Jaintia families. She was the major deity worshipped by the Jaintia royal family during the 16th century after consolidating its sway over the plains tracts in the south.

The present-day Jaintia Hills District in Meghalaya constituted the nucleus around which the Jaintia Kingdom grew and prospered. Slowly, this Kingdom began to play an increasingly important role in the politics and culture of the North-East from the 17th century onwards. The Jaintia kings initially ruled in the hill areas only. But, they gradually extended their territory by means of military conquests both in the areas to the North and the South, but particularly towards the South. Originally, their capital was at Nartiang near the Durga temple although later, they had shifted to the hills of Jaintiapur in the plains of Sylhet (today’s Bangladesh).

Located in the West Jayantia Hills, the Nartiang Durga temple at Jowai, Meghalaya is one among the fifty-two Saktipeeths of Bharat, where Devi is worshipped as Ma Jayanti or Jayanteswari. The Devi’s left thigh is believed to have fallen at Nartiang. According to the head Pujari of this temple, several Sakti worship rituals that are followed here are similar to the Bhadrakali temples of Kerala. The present structure of the Durga Nartiang temple was built during the 15th century when a Koch princess Lakshmi Narayan, daughter of Koch Raja Naranarayan, married the Jaintia King Jaso Manik.

It is said that the King had a vision of the deity in his dream who had asked him to build a temple there. Jaso Manik had extended the territories of his Kingdom bordering the Ahom dynasty of the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam to include the smaller Kingdoms of Gobha, Nelle, Khola, Topakuchi, Baropujia, Sahari, and Phulaguri. These Kingdoms are now a part of the Kamrup and Nagaon districts of Assam. Jaso Manik was also known to have maintained friendly relations with Vijay Manikya, the King of Tripura. The Ahom Swargadeo (King akin to a Devata) Pratap Singha, a devout Hindu, also maintained cordial relations with the Jaintias.

Inside the Durga temple at Nartiang village, Jowai, Meghalaya

Ma Jayanteswari was the presiding deity of the Jaintia royal family and a central figure of the Niam-Tre belief system, the religious rites and rituals of which are quite similar to Hindu Dharma, especially in matters related to birth and death. Just like in any other ordinary Hindu family, they cremate their dead unlike the Christians. They also have similar customs for rituals related to marriage and pregnancy. Hindu Jaintias of Meghalaya are primarily concentrated in the towns of Mihmyntdu, Jowai, and Nartiang. A declining religious belief system, Niam-Tre is an ode to Mother Nature’s power to create, nurture and sustain life.

Sakti worship rituals followed in Nartiang are unique. The rituals in the Durga temple at Nartiang, a beautiful fusion of Bengali Hindu and ancient Khasi traditions, are not performed in the conventional way as is the case in the plains. The local priest or Syiem (in the Khasi language) is considered as the chief patron of this temple. The popular belief here is that the locals of the Jaintia Kingdom were not familiar with the Puja rituals, and since they could not find any Brahmin from neighbouring Assam to preside over these rituals, they decided to invite the Deshmukh Brahmins (known as Deshmukhiyas among the Jaintias) from Ujjain, Maharashtra and other parts of Western India as pujaris.

Currently, it is the 30th generation of these pujaris who are looking after the day-to-day functioning of the temple. Their forefathers were settled in the area encompassing Sylhet in present-day Bangladesh. Jaintia native priests are called Lyngdohs while Jayantia Brahmins are known as Wamons, who are seen as natives because of the matrilineal system that they follow. Bali-pratha is one of the commonest and popular modes of Sakti worship at the Nartiang Durga temple too. Goats, pigeons, and ducks are the most common animals sacrificed on the day of Maha-Astami during the annual Durga Puja celebrations.

Earlier, the temple used to attract a large number of pilgrims on the occasion of Durga Puja, which is the most important festival observed here. But, over the past few years, in the words of Anil Deshmukh, the mukhya pujari of this temple, “There has been a continuous decrease in the number of visitors to this temple.” Just like in any other part of Eastern India, among the Hindus of Meghalaya too, Mahalaya marks the onset of Durga Puja. It heralds the end of the Pitru Paksha period and the advent of Devi Paksha. Sakti worship is prevalent among the Hindu Khasis of Shella (Sohra/Cherrapunji) and the Jaintias of Nartiang village.

While some among them follow a sattvic diet regime from the onset of Mahalaya, some do it from the day of Shasti. Khasi practitioners of Niam-Tre give offerings to Hindu deities as well, but only very few among them consider themselves as Hindu. They rather perceive themselves to be ‘indigenous’ rather. Along with Ma Durga, they also worship Ka Lukhimai, an indigenized variant of Devi Laxmi. On the contrary, however, a significant section of the non-Christian population among the Jaintias takes pride in their Hindu identity. Even today, we can see many Jaintia homes plastered with cow-dung, seemingly because of Hindu influence.

During the Durga Puja festivities at Nartiang, the trunk of a banana tree is worshipped as Ma Durga. Decked in fresh marigold flowers and white linen, it is beautifully dressed as Durga in a red saree and decorated with traditional ornaments by the chief Pujari (Syiem) of the temple. The traditional Ka Pastieh Kaiksoo dance of the Jaintias is always performed during the Durga Puja celebrations. The bhog offered to the Devi is prepared by the local Khasi and Jaintia village women. At the end of the five-day festivities on the day of Visarjan, the banana trunk with all its clothes and jewels is ceremoniously immersed in the nearby Wah Myntang river.

The Jaintias believe that after Visarjan, Devi Durga returns to Her abode in Kailash which is commonly known among them by the Khasi name of Ki Lum Makashang. Darpan Visarjan is another important ritual that is observed at the Nartiang Durga temple before the actual immersion of the murti. In this ceremony, the Syiem symbolically immerses the murti (the banana trunk) by capturing its reflection in a bowl of water. One has to see the reflection of Ma Durga through this bowl to attain Her blessings. Although this had been the practice traditionally, it is, however, now on the decline.

Sakti worship among the Hindus of Meghalaya would remain incomplete without a mention of the most revered sacred groves of Mawphlang village in the East Khasi hills district of the state. People of this region believe that in these forests reside Labasa – a local deity who has played a key role in preserving nature. The locals here are of the firm belief that it is Labasa who protects their forests and community from any mishap. Labasa is believed to take on the form of a leopard or tiger, and protect the village. The Mawphlang sacred groves have one strict rule – ‘Nothing is allowed to be taken out of here. Not even a leaf, stone, or a dead log’.

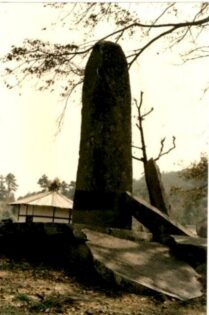

Monoliths at Nartiang village, Meghalaya. In the Khasi hills of Meghalaya, the sacred groves are locally known as Lav Kyntang, Lav Niam or Lav Lyngdoh, Khloo Blai in the Jayantia hills, and Asheng Khosi in the Garo hills.

Cutting any plant or removing even the tiniest leaf from these forests means disrespect to Labasa who is believed to be the all-round protector of every living being in the Universe. It is said that whoever attempts to break this rule is punished with a fatal illness or even death in extreme circumstances. Every sacred forest in and around the villages of Nartiang and Jowai in Meghalaya has the presence of a sacred altar, mostly in the form of a monolith, covered on all sides by massive stones which were constructed by the Hindu Jayantia kings to mark their victories.

The tallest monolith at Nartiang

Sakti worship was also an integral part of the traditional Naga belief systems. The Hindu Zeliangrong (a term used to refer to a collection of three tribes – Zeme, Liangmei, and Rongmei) Nagas of Assam’s Cachar region Manipur’s Tamenglong district, and Peren district of Nagaland, have preserved it in different forms till date. Besides Durga Puja, they celebrate Hindu festivals like Maghi Purnima and Sivaratri. Although more than 96% of the Nagas in present-day Nagaland identify themselves as Christian, the last remaining non-Christian population of Angami Nagas at Viswema village have still adhered to their ancestral beliefs and traditions.

Even today, they consider the norms and rituals practised by their forefathers as sacred. They follow a system known as genna – a set of intricately evolved religious beliefs and rituals, associated with do’s and dont’s for people of different genders and age-groups. This culture of the non-Christian Angami Nagas has been sustained through oral traditions passed over several generations. They believe in Kupenuopfu, who is worshipped as the Creator through various oblations, sacrifices, and chants. Kupenuopfu has a feminine connotation among the Angamis, as the one who is responsible for the process of life-giving, i.e. birth or creation.

Kupenuopfu, it is believed, incorporates both the masculine and the feminine aspects of Creation. Men and women in Naga families who worship Kupenuopfu are expected to follow different sets of rites and rituals, and adhere to certain norms of eating and fasting in their daily lives. Women are largely responsible for conducting the main religious rituals and observe fasting. The chief priest, usually the eldest member in the community, announces the rules for the day at dawn and anyone who does anything that is prohibited as per the religious rules and regulations, is meted out the appropriate punishment.

Traditionally, both feasting and fasting play a significant socio-cultural role in the lives of the Nagas even today. An important aspect of Kupenuopfu is that there is no binary concept of virtue or sin. It is not considered a sin if a mistake is committed unknowingly. However, it becomes a grave sin if the mistake is committed knowingly and genna is not observed. Before the advent of Christianity, the Angami Nagas also used to worship Miawenuo, a Devi believed to grant all the wishes of Her devotees’. The Sumi Nagas worshipped another female deity called Litsaba for good reproductive health and protection of crops from pest attacks.

Litsaba is invoked during the annual post-harvest festival of Tuluni celebrated in July. It is forbidden for anyone to work in the fields that day. Among the Hindu Zeliangrong group of Nagas, the Zeme Nagas worship a male deity called Rampaube along with His female consort Tengrangpui who is invoked as the Sakti. The Zemes believe that Rampaube and Tengrangpui reside at Mount Pauna (Nagaland’s third highest peak), which incidentally happens to be the home of a ginseng-like medicinal herb believed to bring the dead back to life. The Zeme and the Liangmei groups of Nagas are also sometimes together referred to as Kacha Nagas by the locals.

The non-Christian Zeliangrongs, at present, follow three different belief systems – Heraka, Poupei Chapriak (in Assam), and Tingkao Ragwang or simply Tingwang (in Manipur), who is equated with Mahadev and worshipped as the Supreme Deity by the Zeliangrongs. Although Heraka is monotheistic in nature, it does not deny the existence and worship of other Gods and Goddesses. Poupei Chapriak and Tingwang, on the other hand, are polytheistic. The Zeliangrongs have their own prayer centres called Kalum/Karum Kai and temples known as Rakai.

Mount Koubru in Manipur’s Kangpokpi district, believed to be the abode of Tingkao Ragwang, is regarded as sacred by the Zeliangrongs. A small section of the Hindu Zeliangrong Nagas in Assam’s Silchar worship Siva as Bhuban Baba at the sacred Bhuban cave. They celebrate a grand festival on the auspicious annual occasion of Maghi Purnima at the Naga Bisnu temple (Naga Bisnu Rakai) situated atop the Bhuban hills. A Mahadev temple (worshipped as Bhubaneswara) situated adjacent to it could possibly have been built by the Dimasa, Tripuri, or Koch kings, as the locals believe. Zeliangrongs also worship deities such as Laxmi and Ganesha.

Inside the Naga Bisnu temple at Bhuban Pahar, Silchar

The word Bhuban is a derivative of the Rongmei Naga word Pubuan, referring to Apoubaomei Bhuanchaniu, one of the deities worshipped by the Zeliangrongs. Pubuan/Bhuban hill is the abode of Apoubaomei Bhuanchaniu, in whose honour an annual pilgrimage is observed on the occasion of Maha Sivaratri under the guardianship of the elders of the Hindu Zeliangrongs of Assam, Nagaland, and Manipur. Apoubaomei Bhuanchaniu is worshipped at the cave of Bhuban Baba located in the Bhuban hills (also known as the Naga cave).

In the dense forests of the Bhuban hills, archaeological remnants of several Hindu Rongmei Naga villages which existed in the past, have been found. A cultural aggression has been unleashed upon these communities by several anti-India, external elements to give up their Hindu way of lives. The brutal assassination of the then Chairman of the Barak Valley Hill Tribal Development Council, Babul Rongmei, in 2011 by terrorists of the dreaded National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) is a case in point. It had later come to light that Babul Rongmei’s promotion of the traditional belief systems of the Nagas was posing a direct threat to the NSCN.

Stones dedicated to Apoubaomei Bhuanchaniu, found on way to the Bhuban hills

In another spine-chilling incident, the Manmasi National Christian Army (MNCA), a Christian insurgent outfit, was charged with forcing the Zeliangrongs of Bhuban hills, Silchar to convert at gunpoint in the year 2009. Around 7-8 Hmar Christian radicalised youth, all dressed in black with a red cross painted on their backs and armed with sticks, assault weapons and rifles, visited Bhuban Pahar to pressurise the Nagas to convert. When they refused, the rebel leaders desecrated their temples (around 8) by painting symbols of crosses on the walls with their own blood, claiming that it represented their living ‘warrior God’ or Jesus Christ.

Local Hindus feeding animals outside the Naga Bísnu temple in Bhuban Pahar, Silchar

Later, the Sonai Police and the 5th Assam Rifles had arrested 13 members of the MNCA, including their Commander-in-Chief. Guns and ammunitions were also seized. It may be noted here that Haipou Jadonang, the Hindu Rongmei Naga leader and freedom fighter, worshipped Visnu and Tingkao Ragwang at the Bhuban cave. The Zeliangrongs worship Visnu as the chief deity of welfare and all-round prosperity even today. In the Zeliangrong religious pantheon, Visnu is known by different names such as Monchanu, Bonchanu, Bisnu, Buisnu, etc.

Seen at the entrance of the cave of Bhuban Baba located in the Bhuban hills of Silchar

The tradition of Sakti worship in the North-East would remain incomplete without a mention of Devi Tripurasundari, who is worshipped in many temples across India, noteworthy being the Tripura Sundari Saktipeeth. Located in the ancient city of Udaipur, about 55 km from Agartala, Tripura, Tripura Sundari is one among the 52 Saktipeeths of Bharat. According to the popular story of Sati’s death by self-immolation, her right leg had fallen here. Tripura Sundari is worshipped by all people of Tripura, including the Twipras (Debbarmas, Reangs, Jamatias, Murasings), the Hindu Bengalis, and the Tripura royal family.

The Tripura Sundari temple is built atop a hillock, which is in the shape of the back of a tortoise (kurma). In the Sakta parampara of Hindu Dharma, this is believed to be one of the most sacred sites for a Saktipeeth to be located. According to a story associated with the temple on Sakti worship and as written in the Rajmala (the historical chronicle of Tripura), King Dhanya Manikya who ruled over Tripura in the closing years of the 15th century, had a revelation one night in a dream. Devi Bhagawati instructed him to shift Her murti from Chottogram (present-day Chittagong) and initiate Her worship on the hillock near Udaipur, the then capital of the kingdom.

The king found out that a temple on the hillock was already dedicated to Visnu. He was in a dilemma, unable to decide how a temple dedicated to Visnu could have a murti of Sakti. The following night, the divine vision was repeated again, with Tripura Sundari coming along with Brahma, Visnu and Maheswara. The King understood that Visnu and Sakti were different swaroopas of the same Brahman. Thus, the temple of Tripura Sundari in present-day Agartala is believed to have come into being. It is revered as the place of convergence of all Vaisnava and Sakta worshippers. Mata Tripuresvari is called Motai Thakurani in the native Kokborok language.

The Chaturadasa temple (Chaturadasa literally meaning ‘the temple of 14 deities’) is another popular Hindu religious place of worship in Tripura where 14 Kokborok deities (important deities of the Tripura royal family) are worshipped. These deities include – Brahma, Visnu, Siva, Durga, Laksmi, Kartikeya, Saraswati, Ganesa Samudra, Prithvi, Agni, Ganga, Himadri, and Kamadeva. They are known by the local names of Burasa, Lampra, Bikhatra, Akhatra, Thumnairok, Sángroma, Bonirok, Twima, Songram, Mwtaikotor, Mailuma, Noksumwtai, Swkalmwtai, and Khuluma respectively.

The historical belief is that the mother of Raja Trilochan who was the king of Tripura, had saved these 14 deities from being killed by a wild buffalo when she went to take a bath in the Maharani river. The deities eventually killed the beast with her help. Happy with the efforts of the King’s mother, they visited his palace in Udaipur. The royal family offered Puja to all these deities and also sacrificed wild buffaloes. Kharchi Puja is a century-old Hindu religious festival celebrated annually at this temple during the month of Aashad (June-July), 15 days after the end of the Ambubachi celebrations (yearly menstrual cycle of Devi) at the Kamakhya Sáktipeeth.

A beautiful amalgamation of Vedic Hindu and local Kokborok customs, the festivities of Kharchi Puja are held for around a week and sometimes even more. During this Puja, goats, pigeons, and buffaloes are sacrificed to propitiate the Devi with blood. Kharchi Puja is believed to be a way of purifying Bhudevi or Mother Earth after Ambubachi. During the celebrations of Kharchi Puja, thousands of people from not only Tripura but also various other parts of the country could be seen taking a parikrama and circling around the Chaturadasa Devta temple. The word Kharchi is derived from two different words – Khar which means sin; and, Chi meaning cleanliness.

Together, it means the cleansing of sins committed by the people. The rituals of Kharchi Puja begin after the Raj chantai (mukhya Pujari) and his fellow Pujaris take the 14 deities to the nearby Saidara river, which is followed by a bath in the sacred waters. The deities are then brought to the temple, decorated with flowers and vermilion applied to their foreheads. The popular belief is that Kharchi Puja was started in 1760 AD by the then Maharaja of Tripura Krishna Manikya Bahadur. Since then, this festival became an annual event in Tripura, continuing in full spirit till the present times.

Cultural programs are organized in the evening during the entire 7-day period of the celebration of Kharchi Puja. A fair is also organized to commemorate the occasion. Two weeks after the end of Kharchi Puja in Tripura, another popular festival known as Ker Puja is celebrated in honour of Vastu Deváta. People believe that the former rulers of the past used to perform this Puja for the general welfare and well-being of the people of their state. Ker is considered as the guardian deity of Vastu Devata. A large piece of bamboo bent in a particular fashion assumes the image of Ker, and it is fast rotated to produce a sound.

The literal meaning of Ker is a boundary or specified area from where no one is allowed to enter or come out for two and a half days during the celebration. The Chantai is regarded as the king of the occasion. Celebrated amid great fanfare with financial support from the State Government of Tripura, Ker Puja is associated with various traditional beliefs and practices of the people of Tripura. The religious rituals of the Puja begin early in the morning, with offerings of meat and blood being made to the deity. Pregnant women, aged and ailing people are shifted to the neighbouring villages before the beginning of the Puja ceremonies.

Ma Tripura Sundari, also known as Soroshi or Chhoto Ma among the Hindus of Tripura

Some locals are of the belief that Her murti was found submerged in a water-body by King Dhanya Manikya.

Chaturdasa temple and the Raj Chantai inside the temple, Tripura

People in the surrounding areas are not allowed to step beyond the demarcated boundary till the Puja is over. If any person enters the boundary by mistake, he/she is not allowed to move back from the place. The devotees engage in dancing and feasting in the evening after the Puja comes to an end. It may be mentioned here that Ker Puja was originally performed to protect people from diseases, poverty and destitution, natural calamities, and external aggression such as wars. Tripura police personnel fire guns before the beginning of the rituals of Ker Puja and as well as at the end of it.

As a result of the proselytisation activities of the Christian missionaries in the North-East, the traditional ways of lives and belief systems of the people are on the decline. Some have managed to survive, while others have already faced a slow death. The Hindu heritage of North-East India is a less talked-about subject, and Sakti worship in different forms constitutes an integral part of this heritage. Prior to the advent of Christianity in the North-East, each state of this region had their own unique system of worship of local Devis and Devatas rooted in their own traditions and religious belief systems.

Both Siva and Sakti constituted an integral part of these belief systems. The states of Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Mizoram have almost lost these Dharmic traditions forever. They, however, still continue to survive in neighbouring Arunachal Pradesh, especially among the Hindu Noctes, Wanchos, and Apatanis. The Konyak Nagas of Haanhsora Aadorxo Naga Gaon in Sivasagar district of Upper Assam, who follow the Mahapurusiya Naam Dharma tradition of Srimanta Sankardeva, also stand out in this regard. In Mizoram and Tripura, the Hindu Jamatia, Reang, and Hajong communities are continuously battling a daily struggle for existence.

Tripura’s border with Bangladesh in Agartala

In the face of these and numerous other challenges such as drug trafficking and illegal immigration, it is now all the more important to work towards the preservation of the traditional systems of religious beliefs and practices of these people. Although influenced by various local elements, these practices and beliefs are not different from that of the Hindus. Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana are an inseparable part of the history and culture of the North-East. The festivals, dance forms, Sakti worship, and all the surviving Hindu religious places of worship in the North-East are proof enough of this fact.

References:

1. B.B. Jamatia. (2011). Religious Philosophy of the Janajatis of Northeast Bharat. Heritage Foundation, Guahati, Assam.

2. C.K. Malsom (ed). Socio-Cultural and Spiritual Traditions of Tripura. Heritage Foundation, Guwahati, Assam, 2011.

3. Hidden Shaktipeeth in Meghalaya and Maratha-Sylheti Connection. Barak Bulletin.

4. Revitalisation of Indigenous Faith in Northeast Bharat, Heritage Explorer. Vol. XIX, No. 7, August 2020. Heritage Foundation, Guwahati, Assam.

All photographs in the article are from the author’s personal collection.

Acknowledgement: A special note of thanks to Biman for enlightening me always with his valuable inputs on the North-East; the library staff of the Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Guwahati; S. Sarma Baruah and Subhajit Choudhury and his family for helping me with my visits to Meghalaya and Tripura respectively.